My second post this Platinum Jubilee week and today I am selecting a book from the 1960s. At the start of the decade the monarchy was still largely revered in British society, but the cracks were beginning to show, not least in the decline of the British Empire. In 1961, the Queen welcomed President John F Kennedy and his wife Jackie Kennedy to Buckingham Palace, a visit that had mixed results.

In this decade the pendulum swung completely the other way from the 1950s and it is the decade everyone associates with sexual liberation, a determined assertion of greater freedom from the young and a general breaking down of assumed norms. The first generation born after the second world war came of age in the 1960s and after the austerity and rationing of the 1950s, it is no wonder that people were looking to express themselves more and to live a different kind of life to their parents. It was also a period of great turmoil; the second world war was long past, but the Vietnam War was in full swing and protests against it by the young proved a major international creative force, particularly in popular culture.

There were some interesting literary milestones in this decade. DH Lawrence’s extraordinary sexual novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover was published in the UK for the first time in 1960 (it had been written in the 1920s, but was only published privately in Paris). The publisher, Penguin, was prosecuted under obscene publications legislation and won a landmark victory. If the authorities were seeking to drive the book out of the public’s hands, the trial served only to draw attention to it and the book became a huge seller. Although the ban was sought ostensibly on the basis of its obscene content, one suspects that the Establishment also feared the ramifications of suggesting that there could be sexual relations across class boundaries. The long-established traditions and social norms were under threat.

The decline of an old way of life is foretold in another landmark British novel published in this decade, Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), about an unconventional teacher at an Edinburgh girls’ school. This book is frequently cited as one of the finest in English and catapulted its author to worldwide literary fame.

The 1960s also saw the rise of one of the greatest children’s writers of all time, Roald Dahl. In this decade he published James and the Giant Peach (1961), Charlie and Chocolate Factory (1964) and The Magic Finger (1966). Dahl changed children’s fiction forever – compare his anarchic books to those of Enid Blyton! Although I have to confess that I rather love both authors! Despite Dahl’s literary brilliance, his legacy is not without controversy.

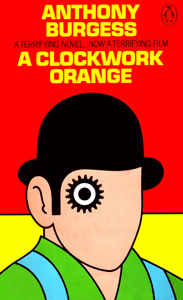

For me, the book of the decade is Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange which was published in 1962. This book is a profound and disturbing novel, a bleak dystopian vision of a society where youth culture is dominated by unrestrained violence and anarchy and where the Establishment response is the most oppressive force and cruelty, as bad as the violence it was trying to suppress. Burgess turns language upside down, reflecting the fact that social order is upside down.

Born in the year of the Russian revolution (1917) in a suburb of Manchester. Burgess lived through interesting times, serving in the second world war, working as a teacher, translator and linguist, and was a composer as well as a writer. Artists of his kind come along rarely, and books like A Clockwork Orange come along rarely. It’s publication was surely one of the literary milestones of the twentieth century. Though I doubt Her Majesty has read it.