I posted a blog last week encouraging you all to give a book a home this Christmas. A well-chosen book is NEVER a bad gift idea. Even if the gift receiver does not in the end like the book they will appreciate you buying it for them, especially if you write something inside about why you chose it. It will also give the two of you something to talk about. It’s the gift that keeps on giving!

Kids can be more tricky, as we know! Unless you know what authors they like, or what sort of reading material they are into, it can be a risk. And for a reluctant reader, receipt of a book may come as a disappointment. When it comes to encouraging children to read, my advice is always to let them choose, but that can be difficult at Christmas, if you are buying for nieces and nephews, for example. Non-fiction is always a good choice in this scenario as you will be able to find a book on almost any subject, targeted at the age range you are looking for. I’ve done a bit of research for you and here are some that have caught my eye.

For younger ones:

Paper Monsters by Oscar Sabini (£14.95). This is a gorgeous gift book. The idea is the child makes a collage on a blank sheet and then uses the monster templates to cut round. There is a similar book Paper Zoo which is just animals.

Barefoot Books World Atlas by Nick Crane & David Dean (£9.99). I love the values and ethos behind Barefoot Books. Multi-cultural and humanitarian themes are present in everything they publish and their books can be valuable tools in combatting exclusion in our world and teaching children about kindness. This world atlas focuses on the interaction between environment and the communities and cultures of the world.

Barefoot Books World Atlas by Nick Crane & David Dean (£9.99). I love the values and ethos behind Barefoot Books. Multi-cultural and humanitarian themes are present in everything they publish and their books can be valuable tools in combatting exclusion in our world and teaching children about kindness. This world atlas focuses on the interaction between environment and the communities and cultures of the world.

For 10-13 year olds:

Illumanatomy by Kate Davies and Carnovsky (£15.00). A superb large format book about the human body that goes into real detail. The illustrations are outstanding; when viewed with the special lenses provided you can see different parts of the body (skeleton, muscles, organs) and how they interact. Perfect for budding biologists!

Illumanatomy by Kate Davies and Carnovsky (£15.00). A superb large format book about the human body that goes into real detail. The illustrations are outstanding; when viewed with the special lenses provided you can see different parts of the body (skeleton, muscles, organs) and how they interact. Perfect for budding biologists!

EtchArt: Hidden Forest by AJ Wood, Mike Jolley & Dinara Mirtalipova (£9.99). This is rather like those books in the colouring trend except the images you create are shiny and sparkly. The child uses the etching tool provided to produce glorious forest-themed pictures (there is also a sea-themed one available). Lovely, and nice and solid.

EtchArt: Hidden Forest by AJ Wood, Mike Jolley & Dinara Mirtalipova (£9.99). This is rather like those books in the colouring trend except the images you create are shiny and sparkly. The child uses the etching tool provided to produce glorious forest-themed pictures (there is also a sea-themed one available). Lovely, and nice and solid.

Older teens:

Notes from the Upside Down: Inside the World of Stranger Things by Guy Adams (£12.99). My teenagers love this show and Season 2 has been hotly awaited in our household! Yes, I know it’s a companion to a TV series, but it’s potentially entry-level Stephen King, which is not necessarily a bad thing.

Wreck this Journal by Keri Smith (£12.99). Yes, I know it’s not exactly a reading book (though there are plenty of words) there are writing and drawing opportunities. I actually love this series as I think they tap into teenagers’ anarchic tendencies, whilst also encouraging a degree of creativity. Here’s the 2017 offering and the cover is much nicer than previous editions. Good fun.

Wreck this Journal by Keri Smith (£12.99). Yes, I know it’s not exactly a reading book (though there are plenty of words) there are writing and drawing opportunities. I actually love this series as I think they tap into teenagers’ anarchic tendencies, whilst also encouraging a degree of creativity. Here’s the 2017 offering and the cover is much nicer than previous editions. Good fun.

If you have any non-fiction suggestions I’d love to hear them.

If you have enjoyed this post , then do follow my blog for more bookish thoughts.

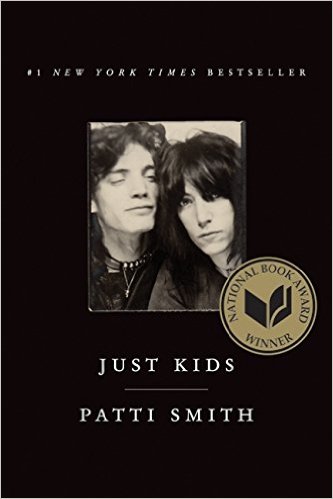

I’ve been an admirer of Patti Smith for a number of years now. I’m a bit young to have been a fan of hers when she first broke onto the music scene in the mid-1970s. I became aware of her much later when I picked up a sale copy of her debut album Horses. I was also aware of Robert Mapplethorpe, the late artist-photographer who was her lover and then close friend when they were both very young. Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989 and it must have been in the 1990s that I saw an exhibition of his work in London (I had an interest in photography at the time). Later on again I learned about the connection between the two and how Patti had been, if you like, Mapplethorpe’s ‘muse’ when he was first discovering his art.

I’ve been an admirer of Patti Smith for a number of years now. I’m a bit young to have been a fan of hers when she first broke onto the music scene in the mid-1970s. I became aware of her much later when I picked up a sale copy of her debut album Horses. I was also aware of Robert Mapplethorpe, the late artist-photographer who was her lover and then close friend when they were both very young. Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989 and it must have been in the 1990s that I saw an exhibition of his work in London (I had an interest in photography at the time). Later on again I learned about the connection between the two and how Patti had been, if you like, Mapplethorpe’s ‘muse’ when he was first discovering his art.

I’m not knocking either of these genres, I’m simply saying that literary non-fiction is a very tough genre to sell in. I read recently that the average non-fiction title in the US sells 250 copies a year (one for roughly every million people), or 2,000 copies over its lifetime. It makes you wonder why on earth you would write one! Many seem to be written by academics, journalists or people who have already established themselves in a chosen field and know they are writing for a particular niche. One striking thing about the genre, though, is that authors have a real passion for the topic, and the authenticity of the work is palpable.

I’m not knocking either of these genres, I’m simply saying that literary non-fiction is a very tough genre to sell in. I read recently that the average non-fiction title in the US sells 250 copies a year (one for roughly every million people), or 2,000 copies over its lifetime. It makes you wonder why on earth you would write one! Many seem to be written by academics, journalists or people who have already established themselves in a chosen field and know they are writing for a particular niche. One striking thing about the genre, though, is that authors have a real passion for the topic, and the authenticity of the work is palpable.

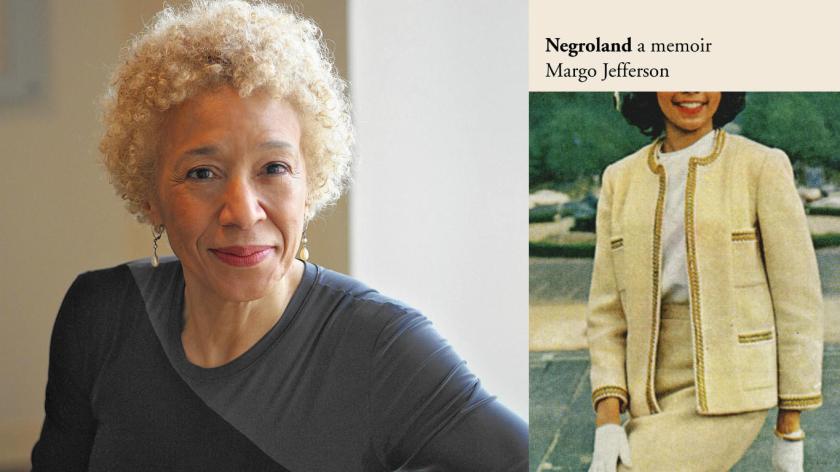

This is a novel about race in modern America where the white population seems to feel it has solved the problem of racism. Firstly, it abolished slavery and then set in place several pieces of legislation to reinforce racial equality. Unfortunately, this has not addressed a fundamental problem of disparity of outcomes between whites and blacks (or people of colour more widely), in academic achievement, income, social status, crime, you name it, the statistics paint a troublesome picture. The thesis of the novel is that, whilst white America is slightly uncomfortable with the facts as they stand, they can point to a number of black high achievers (not least the first African-American President) as evidence that they have done all they could. The under-achievement of the rest can be put down to, for example, their own fecklessness or problems of character.

This is a novel about race in modern America where the white population seems to feel it has solved the problem of racism. Firstly, it abolished slavery and then set in place several pieces of legislation to reinforce racial equality. Unfortunately, this has not addressed a fundamental problem of disparity of outcomes between whites and blacks (or people of colour more widely), in academic achievement, income, social status, crime, you name it, the statistics paint a troublesome picture. The thesis of the novel is that, whilst white America is slightly uncomfortable with the facts as they stand, they can point to a number of black high achievers (not least the first African-American President) as evidence that they have done all they could. The under-achievement of the rest can be put down to, for example, their own fecklessness or problems of character.