The 2017 Man Booker longlist was released yesterday and there are a number of books on the list this year which most avid readers and observers of the book world will recognise. A wide mix of well-known and debut authors, women and men, and diverse countries. So, if you’re looking for some summer reading suggestions, you could do worse than browse the list. I’ve only read Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, which I reviewed here back in June, and which I absolutely loved, but there are plenty of the others in the list that are on my TBR pile, including Arundhati Roy, Mohsin Hamid and Colson Whitehead.

However, I think it is fair to say that when it comes to holiday reading, most of us are usually looking for something a little lighter? (Which Days Without End certainly is not!) Something you can read and enjoy on the beach with one eye on the kids? Something you wouldn’t mind leaving on your holiday rental’s bookshelf? If these are your criteria, I would suggest the following from my most recent reads (the title links through to the reviews).

Firstly, Holding by Graham Norton, which I enjoyed on audiobook (you will too), but which would be equally good as a hard copy and which, for me, is perfect holiday reading. Secondly, Sometimes I Lie by Alice Feeney, a decent thriller which I enjoyed, despite it not being my favourite genre. Thirdly, The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd, which is a lovely life-affirming book.

There are of course, a lot of titles published in the Spring and early Summer, marketed specifically for the holiday reading market. I’ve been perusing the titles and these are the ones that have stuck out for me. The Music Shop by Rachel Joyce, is a love story set in the 1980s about Frank, a record store owner, and Ilse, a German woman whom Frank meets when she happens to faint outside his shop. It’s had good reviews and Rachel Joyce’s earlier novel, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, did very well.

There are of course, a lot of titles published in the Spring and early Summer, marketed specifically for the holiday reading market. I’ve been perusing the titles and these are the ones that have stuck out for me. The Music Shop by Rachel Joyce, is a love story set in the 1980s about Frank, a record store owner, and Ilse, a German woman whom Frank meets when she happens to faint outside his shop. It’s had good reviews and Rachel Joyce’s earlier novel, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, did very well.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman is on my summer reading list. Set in Glasgow, it’s about the emotional and psychological journey of a young woman from shy introvert with a dark past to living a more fulfilling and complete life through friendship and love. I’m looking forward to it.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman is on my summer reading list. Set in Glasgow, it’s about the emotional and psychological journey of a young woman from shy introvert with a dark past to living a more fulfilling and complete life through friendship and love. I’m looking forward to it.

Paula Hawkins’s new novel Into the Water is everywhere, following the phenomenal success of The Girl on the Train which I’ve just finished listening to on audiobook. I had to find out what all the fuss was about! I enjoyed it, but I found most of the characters a bit irritating (that could be the influence of the actors reading, however) and, as I said, thrillers are not my favourite genre. Into the Water is another psychological thriller about a series of mysterious drownings. Like The Girl on the Train, I think, it’s as much about the internal dramas experienced by the characters as it is about ‘events’ so I’m sure it’s gripping.

Paula Hawkins’s new novel Into the Water is everywhere, following the phenomenal success of The Girl on the Train which I’ve just finished listening to on audiobook. I had to find out what all the fuss was about! I enjoyed it, but I found most of the characters a bit irritating (that could be the influence of the actors reading, however) and, as I said, thrillers are not my favourite genre. Into the Water is another psychological thriller about a series of mysterious drownings. Like The Girl on the Train, I think, it’s as much about the internal dramas experienced by the characters as it is about ‘events’ so I’m sure it’s gripping.

Finally, a little-known book that has caught my eye is Your Father’s Room by Michel Deon. Set in 1920s Paris and Monte Carlo (perfect if you’re off to France for your hols!) it is a fictionalised memoir based on the author’s own life. Looking back on his childhood in an unconventional bohemian family during the interwar period, the elderly narrator recounts how the events of his early life, including family tragedy, affected him growing up. I really need to read this; I’m writing a book myself partly based on my grandmother’s life in East London in the same period so I think I could learn a lot from how the author approaches this genre.

Finally, a little-known book that has caught my eye is Your Father’s Room by Michel Deon. Set in 1920s Paris and Monte Carlo (perfect if you’re off to France for your hols!) it is a fictionalised memoir based on the author’s own life. Looking back on his childhood in an unconventional bohemian family during the interwar period, the elderly narrator recounts how the events of his early life, including family tragedy, affected him growing up. I really need to read this; I’m writing a book myself partly based on my grandmother’s life in East London in the same period so I think I could learn a lot from how the author approaches this genre.

I hope you have found these suggestions helpful. If you have any of your own, I’d love to hear them.

If you have enjoyed reading this post, I would love for you to follow my blog by clicking on the subscribe button below or to the left. You can choose to receive a weekly digest of my posts (I usually write twice a week), or get notifications direct to your Inbox as soon as I publish.

I am an admirer of Gillian Anderson, not since her X-Files days, but since watching The Fall, the hugely popular television drama about a misogynistic and brutal serial killer in Northern Ireland, in which Anderson played the beautiful, enigmatic, but also rather damaged DSI Stella Gibson. The drama ran for three series between 2013-2016 and I was hooked. (It also starred Jamie Dornan, which helped). Jennifer Nadel, Anderson’s co-author, is a former journalist, writer and activist. Both women are open about their experiences of depression and poor self-esteem, despite their hugely successful careers and enviable lifestyles, and this book is their account of recovery and a ‘guidebook’ for other women who may be suffering from mental health issues.

I am an admirer of Gillian Anderson, not since her X-Files days, but since watching The Fall, the hugely popular television drama about a misogynistic and brutal serial killer in Northern Ireland, in which Anderson played the beautiful, enigmatic, but also rather damaged DSI Stella Gibson. The drama ran for three series between 2013-2016 and I was hooked. (It also starred Jamie Dornan, which helped). Jennifer Nadel, Anderson’s co-author, is a former journalist, writer and activist. Both women are open about their experiences of depression and poor self-esteem, despite their hugely successful careers and enviable lifestyles, and this book is their account of recovery and a ‘guidebook’ for other women who may be suffering from mental health issues. This is actually my July reading challenge book, which was to borrow something from the library. I read it in virtually one sitting on a train journey to London. For a weighty non-fiction book it’s very readable and the writing is resonant of Evan’s relaxed and articulate presenting style. There were parts where I could almost hear him reading it out. There are many references to the help and support he has had in the acknowledgements, so I’m sure he had plenty of research assistance (how could he not – with Newsnight, The Bottom Line and Dragon’s Den he is a very busy fellow!), but the authorial voice is definitely authentic, and I would bet it isn’t ghost-written, which just makes me love him all the more!

This is actually my July reading challenge book, which was to borrow something from the library. I read it in virtually one sitting on a train journey to London. For a weighty non-fiction book it’s very readable and the writing is resonant of Evan’s relaxed and articulate presenting style. There were parts where I could almost hear him reading it out. There are many references to the help and support he has had in the acknowledgements, so I’m sure he had plenty of research assistance (how could he not – with Newsnight, The Bottom Line and Dragon’s Den he is a very busy fellow!), but the authorial voice is definitely authentic, and I would bet it isn’t ghost-written, which just makes me love him all the more! I fell in love with Jane Austen in my teens, and I have never fallen out of love with her. The first book I read was Pride and Prejudice, and I remember I much preferred this colourful collection of sisters to Louisa May Alcott’s in Little Women! But it wasn’t until I read Emma for my English Literature A level that I really ‘got’ Jane Austen and I was blown away. Even now when I read Austen I still see her writing as impossibly brilliant. And then when you think about the life she led, her modest rural upbringing, her insight into human character is barely plausible. After Emma I quickly gobbled up all of Austen’s work (sadly, there is too little of it) and my favourite is probably Mansfield Park.

I fell in love with Jane Austen in my teens, and I have never fallen out of love with her. The first book I read was Pride and Prejudice, and I remember I much preferred this colourful collection of sisters to Louisa May Alcott’s in Little Women! But it wasn’t until I read Emma for my English Literature A level that I really ‘got’ Jane Austen and I was blown away. Even now when I read Austen I still see her writing as impossibly brilliant. And then when you think about the life she led, her modest rural upbringing, her insight into human character is barely plausible. After Emma I quickly gobbled up all of Austen’s work (sadly, there is too little of it) and my favourite is probably Mansfield Park.

Children these days have so many distractions which can take them away from reading; they seem to be so busy with out of school activities, have more homework than ever before and, of course, there are the digital distractions…don’t even get me started. But reading is such an important activity for them:

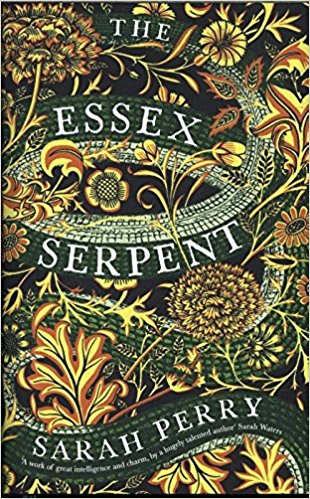

Children these days have so many distractions which can take them away from reading; they seem to be so busy with out of school activities, have more homework than ever before and, of course, there are the digital distractions…don’t even get me started. But reading is such an important activity for them: The book is set mostly in the fictional Essex village of Aldwinter in the 1890s and the action takes place over the course of a year. The central dynamic of the plot is the relationship between Cora Seaborne, a woman approximately in her late 30s, who at the start of the novel is newly widowed, and William (Will) Ransome, the local minister. Will is happily married to Stella and they have three children, while Cora is happily widowed! It seems hers was a fairly loveless marriage in which she felt constrained and imprisoned and her husband appears to have been somewhat older than her. The lack of intimacy in the marriage is indicated by the fact they had only one child, Francis, and that he is an unusual boy (for Cora “nothing shamed her as much as her son”), who is almost certainly autistic.

The book is set mostly in the fictional Essex village of Aldwinter in the 1890s and the action takes place over the course of a year. The central dynamic of the plot is the relationship between Cora Seaborne, a woman approximately in her late 30s, who at the start of the novel is newly widowed, and William (Will) Ransome, the local minister. Will is happily married to Stella and they have three children, while Cora is happily widowed! It seems hers was a fairly loveless marriage in which she felt constrained and imprisoned and her husband appears to have been somewhat older than her. The lack of intimacy in the marriage is indicated by the fact they had only one child, Francis, and that he is an unusual boy (for Cora “nothing shamed her as much as her son”), who is almost certainly autistic.

If, like me, you find yourself a little nostalgic for an era when travel meant slowing down, getting to know a place and its people (rather than just taking a selfie with a local and posting to Instagram), and immersing yourself in the new environment, then Dervla Murphy could be the travel writer for you. In On a Shoestring to Coorg, Murphy travels for the first time with her five-year old daughter, Rachel. They travel scarily light (I would take more stuff on a day out when my kids were younger!) with very little money and are dependent on the kindness and hospitality of people they meet, including a number of British ex-pats, who have made India their home in the post-colonial era.

If, like me, you find yourself a little nostalgic for an era when travel meant slowing down, getting to know a place and its people (rather than just taking a selfie with a local and posting to Instagram), and immersing yourself in the new environment, then Dervla Murphy could be the travel writer for you. In On a Shoestring to Coorg, Murphy travels for the first time with her five-year old daughter, Rachel. They travel scarily light (I would take more stuff on a day out when my kids were younger!) with very little money and are dependent on the kindness and hospitality of people they meet, including a number of British ex-pats, who have made India their home in the post-colonial era.