There is a great deal of debate and attention on the UK National Health Service at the moment as it celebrates its 70th anniversary this year. If you live in Britain, you can’t move for television, radio and newspaper commentaries at the moment. But the talk is not just about celebration, but about what we want and expect public services to provide in the way of healthcare, and, just as important, how the immense costs of it all should be met. The challenges are mind-boggling: we have an ageing population, advanced medicines come at a high price, the long-term nature of public health investment, not to mention dealing with developed world problems such as obesity, addiction and mental illness. The issues are massive.

The NHS was described by politician Nigel Lawson as “the closest thing the English people have to a religion” and it is indeed dear to the hearts of many. Observe the profile it enjoyed at the opening ceremony to the London 2012 Olympics and the influence the promise of extra cash for the NHS most likely had on the Brexit debate.

I have no intention of starting a political debate here, but if health is on your mind, you might want to dip into some books with a medical theme. Here are some of my suggestions (not all of which I have read, I should add):

- Still Alice by Lisa Genova – a moving account of a 50 year-old woman’s development of early onset Alzheimers. Made into a film starring Julianne Moore.

- Everything Everything by Nicola Yoon – a YA book about a young woman suffering from a rare condition which means her immune system is dangerously impaired.

- The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby – a harrowing true story where the author developed locked-in syndrome after a car accident. He was initially thought to be in a coma, but was in fact fully conscious. He was eventually able to communicate through blinking, and wrote this book using only this tool. Incredible and reminds you of the fragility of life.

- The Fault in Our Stars by John Green – another YA novel, both my daughters love this book, about teenage terminal illness. Also made into a tear-jerker of a film.

- This Is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay – award-winning non-fiction writing from a junior doctor telling it like it is on the NHS front-line.

- Call the Midwife by Jennifer Worth – love the TV show, currently reading the follow-up Farewell to the East End, Worth was a young midwife in East London in the 1950s so for a taste of the early days of the NHS look no further.

- Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman – a young Scottish woman’s mental illness, compounded by loneliness, detachment and the harshness of modern life.

- The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon – challenging life events, seen through the eyes of a young man with Asperger’s Syndrome. A must-read.

- Two Girls, Fat and Thin by Mary Gaitskill – I have recommended this book so many times. It’s an intense novel about eating disorders, mental health and sexuality.

If you have suggestions for any other books with a medical theme that you have enjoyed, I would love to hear them.

If you have enjoyed this post, do follow my blog or connect with me on social media.

I have learnt my lesson and carve-out reading time for myself in the day. My bedtime reading is usually reserved for lighter books, entertainment. I have recently discovered the Maisie Dobbs series by British-American writer

I have learnt my lesson and carve-out reading time for myself in the day. My bedtime reading is usually reserved for lighter books, entertainment. I have recently discovered the Maisie Dobbs series by British-American writer  Browsing in the bookshop last year, I noticed that she had published her own autobiography, at the age of 83 – I note with some pleasure that her 84th birthday is in fact today! Many happy returns! Reading the blurb whetted my appetite – I was not aware of her life as a groundbreaking Literary Editor at the Sunday Times, or that she had five children, including one boy who died as a baby, and another son who was born with severe disabilities, nor that her first husband, fellow journalist Nicholas Tomalin, was killed in 1973, when her children were still very young. It sounded like a very interesting read.

Browsing in the bookshop last year, I noticed that she had published her own autobiography, at the age of 83 – I note with some pleasure that her 84th birthday is in fact today! Many happy returns! Reading the blurb whetted my appetite – I was not aware of her life as a groundbreaking Literary Editor at the Sunday Times, or that she had five children, including one boy who died as a baby, and another son who was born with severe disabilities, nor that her first husband, fellow journalist Nicholas Tomalin, was killed in 1973, when her children were still very young. It sounded like a very interesting read. The novel is set in Renaissance Florence; the sense of time and place is profound. You can almost smell the streets wafting from the pages! Dunant is a meticulous researcher and the novel feels very authentic. The central character is Alessandra, the fifteen year-old daughter of a wealthy cloth merchant. Much to the frustration of her family Alessandra is a precociously intelligent young woman, a talented artist, a strong personality and has a deep desire to be out in the world. These are all traits which are highly inconvenient for the family and not compatible with the kind of life she will be expected to lead.

The novel is set in Renaissance Florence; the sense of time and place is profound. You can almost smell the streets wafting from the pages! Dunant is a meticulous researcher and the novel feels very authentic. The central character is Alessandra, the fifteen year-old daughter of a wealthy cloth merchant. Much to the frustration of her family Alessandra is a precociously intelligent young woman, a talented artist, a strong personality and has a deep desire to be out in the world. These are all traits which are highly inconvenient for the family and not compatible with the kind of life she will be expected to lead.

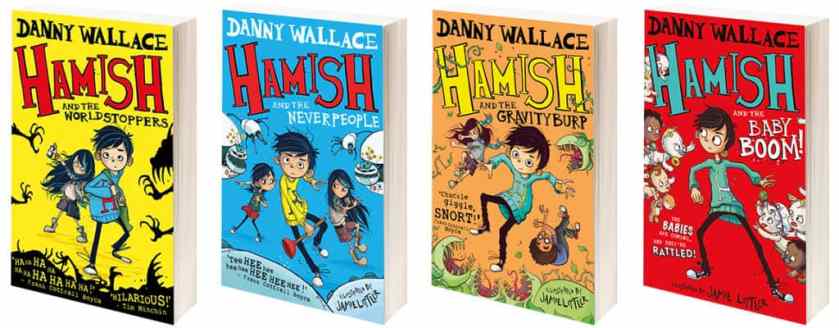

I am a firm believer that all reading material is good, just keep them at it, and adults should not judge if their kids want to read comics and picture books when they might think they ‘should’ be reading something more mature. If this sounds like a child you know, I’ve found a great little series they might find interesting. Hamish and the Baby Boom by Danny Wallace and illustrated by Jamie Littler is the fourth book in a series. Hamish Ellerby is the central character, a 12 year-old boy and leader of the Pause Defence Force in the town of Starkley. Hamish’s father is some sort of secret agent, ever engaged in defending earth against the evil Scarmash. Hamish has inherited some of his father’s abilities and leads his small group of friends in the PDF against strange and hostile happenings in the town of Starkley.

I am a firm believer that all reading material is good, just keep them at it, and adults should not judge if their kids want to read comics and picture books when they might think they ‘should’ be reading something more mature. If this sounds like a child you know, I’ve found a great little series they might find interesting. Hamish and the Baby Boom by Danny Wallace and illustrated by Jamie Littler is the fourth book in a series. Hamish Ellerby is the central character, a 12 year-old boy and leader of the Pause Defence Force in the town of Starkley. Hamish’s father is some sort of secret agent, ever engaged in defending earth against the evil Scarmash. Hamish has inherited some of his father’s abilities and leads his small group of friends in the PDF against strange and hostile happenings in the town of Starkley.