I have had a copy of Alias Grace on my bookshelf for years; my copy might even date back to when the paperback version came out in 1996. But, like so many of the books I own, it was some time before I got around to reading it! I watched the mini-series available on Netflix (it was made in 2017) during the Covid lockdown, I think, and thoroughly enjoyed it so I suppose I felt I didn’t need to read the book after that, but I came back to it recently and am so glad I have finally properly honoured this incredible piece of writing.

Full disclosure, I am a huge admirer of Margaret Atwood and will probably never dislike anything she has written. She is surely one of the greatest authors alive, with countless awards and prizes to her name, including two Bookers and a PEN lifetime achievement award. I’m not sure why the Pulitzer or Nobel prizes have eluded her – surely The Handmaid’s Tale must be a candidate for both of these. The first book of hers that I read was The Blind Assassin, which won her her first Booker Prize in 2000. It was also the very first audiobook I ever listened to, on tape in my first ever little car! The job I had at the time involved a 90 mile round trip drive three days a week and my husband bought it for me to help pass the time. I felt that book was one of the most brilliant things I had read in years; my first child was a toddler so I did not have a lot of time for reading in my life at that stage – at least not adult reading!

Alias Grace preceded The Blind Assassin. In my opinion, the later book is better, but you do get the sense of an author rising to the peak of her literary powers and experimenting with moving between time periods (which she also does in The Handmaid’s Tale, of course). Alias Grace is the story of a double murder and a young woman convicted for the crime. Grace Marks was a young Irish immigrant to Canada and after the death of her mother (on board the ship) she leaves her drunken abusive father and, much to her guilt and shame, her younger siblings, to get a job as a servant girl. She finds a position with Thomas Kinnear, an unmarried gentleman who is having an illicit affair with his housekeeper, and Grace’s immediate supervisor, Nancy Montgomery.

After the couple are murdered in brutal circumstances, Grace is convicted of the crime along with James McDermott, who also worked for Kinnear. McDermott escapes with Grace, but the pair are soon captured, convicted and sentenced to hang. Grace’s sentence is later commuted to life in prison following appeals by a group of well-meaning supporters who believe she was merely an accessory to McDermott’s wicked plan. She is eventually allowed to work as a servant in the home of the prison governor, because she is a docile and obedient inmate. Her supporters eventually arrange for a psychiatrist, Dr Simon Jordan from America, to interview her over a period of time and to produce a report which they hope will help to secure her release.

Atwood uses these interviews to tell us the story; Grace gives a full account of her life to Dr Jordan, from the beginning, her early childhood in northern Ireland, to her mother’s death, and finally her experiences working for Mr Kinnear and Nancy Montgomery and the murders themselves. For the reader, the question becomes, is Grace a reliable witness? This is a dilemma Dr Jordan finds himself in too. Over the months he spends time with her, he also gets drawn into her world and the patient/doctor boundary becomes blurred.

The book is based on real events – these murders actually took place and Grace Marks was a real woman convicted of the crime in mid-19th century Canada. At the end of the novel, the author gives an account of the facts she has gleaned from contemporaneous and historical sources. No-one really knows exactly what happened; the reader, like others who have investigated this grisly crime, must make up their own mind. But Atwood does not leave her readers dissatisfied (at least not this one!) – she leaves you with a question. And in her subtle portrayal of Grace, she leaves you with enough space to draw whatever conclusion you want. Or to leave you as perplexed as, it seems, everyone else has been.

I recommend this book highly – it’s a really significant literary achievement.

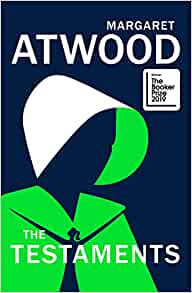

It is truly a groundbreaking novel, but curiously, in my view, less in its own right than as an extension, a continuation of, the work started with the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. What is also partly so extraordinary about The Testaments is how relevant its story remains over thirty years on from The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of equality legislation, human rights legislation, more women in positions of power and authority, we still have world leaders able to express their misogyny openly and with impunity, and violence against women and girls seems as rife as ever. Atwood is Canadian, but her novel is a dystopian vision set in the United States, where, in the last year, we have seen the erosion of women’s reproductive and therefore health rights in some states and the substantial threat of more to come. This novel seems so urgent and necessary.

It is truly a groundbreaking novel, but curiously, in my view, less in its own right than as an extension, a continuation of, the work started with the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. What is also partly so extraordinary about The Testaments is how relevant its story remains over thirty years on from The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of equality legislation, human rights legislation, more women in positions of power and authority, we still have world leaders able to express their misogyny openly and with impunity, and violence against women and girls seems as rife as ever. Atwood is Canadian, but her novel is a dystopian vision set in the United States, where, in the last year, we have seen the erosion of women’s reproductive and therefore health rights in some states and the substantial threat of more to come. This novel seems so urgent and necessary.

The Booker prize winner(s) were announced last week and for the first time in years, and against the explicit rules of the contest, the judges awarded the prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. I have not read either book yet, though I am currently listening to The Testaments on the excellent BBC Sounds and enjoying it enormously, though it is extremely dark. There has been so much publicity around Atwood and The Testaments that I was wondering how on earth the Booker prize judges were going to be able to not award it to her! So, I think the judges probably made the right decision. By now, I would probably have worked my way through at least two thirds of the shortlist (I’ve never managed all six in the period between shortlist and winner), but, for obvious reasons, I have not read that much so far this year.

The Booker prize winner(s) were announced last week and for the first time in years, and against the explicit rules of the contest, the judges awarded the prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. I have not read either book yet, though I am currently listening to The Testaments on the excellent BBC Sounds and enjoying it enormously, though it is extremely dark. There has been so much publicity around Atwood and The Testaments that I was wondering how on earth the Booker prize judges were going to be able to not award it to her! So, I think the judges probably made the right decision. By now, I would probably have worked my way through at least two thirds of the shortlist (I’ve never managed all six in the period between shortlist and winner), but, for obvious reasons, I have not read that much so far this year. It is somewhat and sadly ironic that I was reading Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World at the time of my mother’s death, a novel about a woman, Leila, an Istanbul prostitute known as Tequila Leila, who is brutally murdered in a back alley by street thugs. Rather than death being an instant occurrence, however, the author explores the idea of it as a transition from the world of the living to the ‘other’ (with a duration, for Leila, of ten minutes and thirty-eight seconds) during which time her whole life flashes before her. Leila’s life story is told through a series of recollections about her five closest friends, how and when she met them and what impact they have had on her life. We learn that Leila came from a relatively affluent family. Her father was anxious for heirs, but when his wife proved incapable of having any he took a second wife, Binnaz, a much younger woman from a lowly family, who gave birth to Leila. Binnaz was forced to give up the child to the first wife to bring up as if she were her own, whilst Binnaz, who never recovered mentally from the trauma of that event, was thereafter known to Leila as ‘Auntie’.

It is somewhat and sadly ironic that I was reading Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World at the time of my mother’s death, a novel about a woman, Leila, an Istanbul prostitute known as Tequila Leila, who is brutally murdered in a back alley by street thugs. Rather than death being an instant occurrence, however, the author explores the idea of it as a transition from the world of the living to the ‘other’ (with a duration, for Leila, of ten minutes and thirty-eight seconds) during which time her whole life flashes before her. Leila’s life story is told through a series of recollections about her five closest friends, how and when she met them and what impact they have had on her life. We learn that Leila came from a relatively affluent family. Her father was anxious for heirs, but when his wife proved incapable of having any he took a second wife, Binnaz, a much younger woman from a lowly family, who gave birth to Leila. Binnaz was forced to give up the child to the first wife to bring up as if she were her own, whilst Binnaz, who never recovered mentally from the trauma of that event, was thereafter known to Leila as ‘Auntie’.