I reached a reading milestone recently – I finished Ducks, Newburyport. This humungous novel, which clocks in at a whopping 1030 pages (paperback) is easily the longest book I have ever read. I listened to it on audio, brilliantly read by Stephanie Ellyne, and it lasted over 45 hours, easily the length of six or seven “normal” books. I started it around Christmas time I think, so it has taken me months. I would probably have got through it more quickly in ‘normal’ times as I would have listened to it while driving, but I have hardly driven at all this last year. Mostly I listened to it while cleaning the house, which seemed very appropriate.

The un-named central character and narrator is a middle-aged American woman living in Newcomerstown, Ohio. She is a mother of four, cancer survivor, former college lecturer, and self-employed baker, who makes pies for a number of local cafes and restaurants which she delivers each day. The novel is a written in a ‘stream of consciousness’ style, almost entirely in the present, and many of the sentences begin with the phrase “the fact that…” as she tells us about the various aspects of her life, her family, her husband, her dead parents, their parents, baking, her past career, her cancer and American society. The ‘action’, such as it is, takes place over a short period of time, but, let’s be clear, very little happens in this novel.

It has been criticised for its length; indeed, I read that Lucy Ellmann’s usual publisher, Bloomsbury, declined to publish it for this reason, so instead she went with a small independent, Galley Beggar Press, which is based in Norwich.

The themes of the novel are emptiness and loneliness in modern American life, the dilemmas of being a woman, motherhood, loss. Our narrator commentates scathingly on Trump, on guns, and on the violence in society. She bemoans the decline of childhood, how young people have been lost to technology, social media and advertising and the inequalities not just in American society, but across the world. Yet at the same time, she is a woman who wants the best for her children and therefore perpetuates those inequalities. The essential dilemma. She laments climate change and the loss of the natural world while also contributing to it with her own lifestyle. (As do almost all of us). Yet another modern dilemma. She loves her children, but has a somewhat estranged relationship with her eldest daughter, Stacey, who has a different father to her three siblings.

Mostly, the narrator is grieving; there are frequent pained references to “Mommy”. Her mother died some years earlier after a long illness and the narrator cannot let go of her feeling that she should have done more for her mother, and, mostly, that she misses her terribly. The loss continues to blight her life, and she feels deeply the lack of nurturing she has in her own life. She seems to have a good and loving relationship with her husband, bridge engineer Leo, but it cannot make up for the loss of mother.

There is a parallel story going on in the narrative; a female mountain lion roams Ohio, creating fear throughout the state and leading to a frenzy of trackers and gun-owners who try to hunt her down. She is simply looking for food for her cubs and the reduced wild territory available to her means she trespasses on human occupied land. Our narrator is aware of the lion and fears for her children’s safety, while also virtue-signalling and taking positions on habitat destruction for wildlife. The cubs are captured and taken to the zoo, but the mountain lion continues to search, ceaselessly. Her drive to mother is all-encompassing.

This novel is profound and if you can stick with it, it will reward you handsomely. There is so much complexity, it is so multi-layered. The length also means we bond quite closely with the narrator, in a way that I don’t think would have happened if it had been shorter.

I recommend this book highly, while recognising that few will have the time and opportunity to embrace it. Take a year, six months at least. Get the audio – it is read brilliantly and you can at least do the vacuuming/ironing/cooking as you do so!

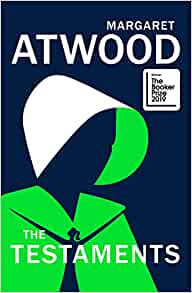

It is truly a groundbreaking novel, but curiously, in my view, less in its own right than as an extension, a continuation of, the work started with the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. What is also partly so extraordinary about The Testaments is how relevant its story remains over thirty years on from The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of equality legislation, human rights legislation, more women in positions of power and authority, we still have world leaders able to express their misogyny openly and with impunity, and violence against women and girls seems as rife as ever. Atwood is Canadian, but her novel is a dystopian vision set in the United States, where, in the last year, we have seen the erosion of women’s reproductive and therefore health rights in some states and the substantial threat of more to come. This novel seems so urgent and necessary.

It is truly a groundbreaking novel, but curiously, in my view, less in its own right than as an extension, a continuation of, the work started with the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. What is also partly so extraordinary about The Testaments is how relevant its story remains over thirty years on from The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of equality legislation, human rights legislation, more women in positions of power and authority, we still have world leaders able to express their misogyny openly and with impunity, and violence against women and girls seems as rife as ever. Atwood is Canadian, but her novel is a dystopian vision set in the United States, where, in the last year, we have seen the erosion of women’s reproductive and therefore health rights in some states and the substantial threat of more to come. This novel seems so urgent and necessary.

What I liked about it, however, was less this grander aspect, but rather the quality of its story-telling. I must admit that 50 or so pages in, I was not overwhelmed! There are twelve characters in the book, all women bar one (who is trans), all black or mixed race. They are broken down into four groups of three, and each threesome is strongly connected in some way (eg mother/daughter). Each group is also connected with the others, even if only in a tenuous way (eg teacher and former pupil) and almost all are in some way connected to Amma, the first character we meet. Amma has written a play which is having its debut performance at the National and this provides the framework of the novel. Many of the characters are present at the penultimate chapter of the book, the after-party, where the differences between them and their lives are laid bare. This is interesting because the author is not only trying to draw out the similarities between the characters and their life experiences, suggested by their common characteristic of being mixed race and female, but she is also, I think, railing against the notion of such women/people being homogeneous; they are all far more than just their race or gender.

What I liked about it, however, was less this grander aspect, but rather the quality of its story-telling. I must admit that 50 or so pages in, I was not overwhelmed! There are twelve characters in the book, all women bar one (who is trans), all black or mixed race. They are broken down into four groups of three, and each threesome is strongly connected in some way (eg mother/daughter). Each group is also connected with the others, even if only in a tenuous way (eg teacher and former pupil) and almost all are in some way connected to Amma, the first character we meet. Amma has written a play which is having its debut performance at the National and this provides the framework of the novel. Many of the characters are present at the penultimate chapter of the book, the after-party, where the differences between them and their lives are laid bare. This is interesting because the author is not only trying to draw out the similarities between the characters and their life experiences, suggested by their common characteristic of being mixed race and female, but she is also, I think, railing against the notion of such women/people being homogeneous; they are all far more than just their race or gender. The Booker prize winner(s) were announced last week and for the first time in years, and against the explicit rules of the contest, the judges awarded the prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. I have not read either book yet, though I am currently listening to The Testaments on the excellent BBC Sounds and enjoying it enormously, though it is extremely dark. There has been so much publicity around Atwood and The Testaments that I was wondering how on earth the Booker prize judges were going to be able to not award it to her! So, I think the judges probably made the right decision. By now, I would probably have worked my way through at least two thirds of the shortlist (I’ve never managed all six in the period between shortlist and winner), but, for obvious reasons, I have not read that much so far this year.

The Booker prize winner(s) were announced last week and for the first time in years, and against the explicit rules of the contest, the judges awarded the prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. I have not read either book yet, though I am currently listening to The Testaments on the excellent BBC Sounds and enjoying it enormously, though it is extremely dark. There has been so much publicity around Atwood and The Testaments that I was wondering how on earth the Booker prize judges were going to be able to not award it to her! So, I think the judges probably made the right decision. By now, I would probably have worked my way through at least two thirds of the shortlist (I’ve never managed all six in the period between shortlist and winner), but, for obvious reasons, I have not read that much so far this year. It is somewhat and sadly ironic that I was reading Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World at the time of my mother’s death, a novel about a woman, Leila, an Istanbul prostitute known as Tequila Leila, who is brutally murdered in a back alley by street thugs. Rather than death being an instant occurrence, however, the author explores the idea of it as a transition from the world of the living to the ‘other’ (with a duration, for Leila, of ten minutes and thirty-eight seconds) during which time her whole life flashes before her. Leila’s life story is told through a series of recollections about her five closest friends, how and when she met them and what impact they have had on her life. We learn that Leila came from a relatively affluent family. Her father was anxious for heirs, but when his wife proved incapable of having any he took a second wife, Binnaz, a much younger woman from a lowly family, who gave birth to Leila. Binnaz was forced to give up the child to the first wife to bring up as if she were her own, whilst Binnaz, who never recovered mentally from the trauma of that event, was thereafter known to Leila as ‘Auntie’.

It is somewhat and sadly ironic that I was reading Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World at the time of my mother’s death, a novel about a woman, Leila, an Istanbul prostitute known as Tequila Leila, who is brutally murdered in a back alley by street thugs. Rather than death being an instant occurrence, however, the author explores the idea of it as a transition from the world of the living to the ‘other’ (with a duration, for Leila, of ten minutes and thirty-eight seconds) during which time her whole life flashes before her. Leila’s life story is told through a series of recollections about her five closest friends, how and when she met them and what impact they have had on her life. We learn that Leila came from a relatively affluent family. Her father was anxious for heirs, but when his wife proved incapable of having any he took a second wife, Binnaz, a much younger woman from a lowly family, who gave birth to Leila. Binnaz was forced to give up the child to the first wife to bring up as if she were her own, whilst Binnaz, who never recovered mentally from the trauma of that event, was thereafter known to Leila as ‘Auntie’.