In my ‘day job’ I work with new parents and parents-to-be, mostly new mothers, supporting them both as they approach birth and in the transition to their new lives with a baby. It is work that I love and have been doing for quite a while now. I also believe it is a role that is increasingly necessary as maternity services and parent support services in the UK are at the lowest ebb I can remember and much worse than when my children were born. Coupled with the mental ill-health epidemic that we seem to be facing, I rather feel that new parents, and new mothers in particular, are having a very tough time.

One of the reasons I have blogged so little in the last few months is that I have been doing additional studying for my work and I came across the first of the two books reviewed below (Matrescence) in the course of this study. It had been on my radar anyway, since it was longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Non-fiction earlier this year, but was on our course reading list. The second book is a novel and was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, but it was coincidence that I happened to read both around the same time.

Matrescence by Lucy Jones

Jones has been a writer and journalist for most of her working life, mostly in the fields of science and nature; her second book, Losing Eden: why our minds need the wild, published in 2020, was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. But it is this account of her parenting journey that has really captured mainstream attention. ‘Matrescence’ is a beautiful word that Jones seems on a mission to bring to the forefront of public attention since it captures the physical, emotional and spiritual transformation that people undergo when they give birth to children. Yes, fathers and co-parents change too, but not nearly as much as mothers. There has been some fascinating research published recently in the US that has looked at the actual way the human brain changes during pregnancy and in the early months of motherhood. The brain seems to stand-down certain areas and functions that it is assumed will be less necessary such as the bits that do tasks, remember things and organise, and boosts the emotional centres, the bits that will make us fall in love with our infant and therefore help assure its survival. Fascinating. But hard in the modern world.

The author’s journey is a very personal one and there were bits that made me bristle (she is critical of pretty much everyone) and I felt a bit personally attacked, having worked in this field for more than 10 years. But there is no doubting that it is meticulously researched and powerfully written. She bemoans the lack of ceremony around the ‘passing into’ motherhood which is particularly the case in western industrial society, and about the failure to both understand what the role really entails and the lack of support. I cannot agree more with this. Where I had more of a problem is where the author seems to believe there is a conspiracy of silence around what it’s really like to give birth and to mother a baby. I don’t think I do agree entirely; I am not sure most people are really ready to hear it plus it is deeply personal and subjective. I do think there is a case for a more open discussion but this would be inconvenient in a western capitalist society where we need to (quite literally) buy into a fantasy, so it probably won’t happen.

Whether you are a parent or not, this book bears reading not least because of how the author brings her knowledge and expertise about the natural world into her writing. Each chapter is prefaced with a snapshot of a reproductive or young-rearing phenomenon from nature, that reminds us we are just creatures on this earth. And that is pretty thought-provoking.

Soldier, Sailor by Claire Kilroy

Matrescence might be the notes that accompany Soldier Sailor so it is fascinating that they should have come out at around the same time. Where Jones is research, science, rage and manifesto, Kilroy is visceral. It is a first-person narrative which is rambling, confused, devoted, passionate and lost. There are no names here, they are unimportant; all that exists is the mother (Soldier) and her baby (Sailor), practically one, almost interchangeable. It’s her and him against the world, and particularly against the husband, who has no clue what is going on. He is a man who at times she loves and hates in equal measure, because her life (the mother life) is changed beyond recognition, and his has not. She cannot hate the child who has caused this transformation so she must rail against the child’s father, a person she no longer recognises and with whom she finds she must learn a new way of being if their relationship is to endure.

There are times when this book is almost unbearable. There are times when it is hard to tell what is real and what is not, distorted by her fevered state of mind. Things that seem real are turned on their head later on. Like the meeting with an old friend from student days in a playground, now a father of four whose wife, who has the greater earning power, works full-time. His experience is the same but different, the flip side of hers, and his balance and calm represent a degree of hope to her that things might one day become normal. Or was the encounter just the work of her imagination, giving her the strength to continue when she has not an ounce of mental or physical energy left and her whole world seems to be falling apart?

There are parts of this book that most mothers would recognise – I certainly felt a frisson at some of the emotions Soldier expressed, they were familiar. But there are other parts, rather like the personal parts of Jones’s account of her mothering journey, that are not universal and it would not be right to think that they are.

It is a powerful read that has garnered a great deal of attention and whilst this book did not win the Women’s Prize this year it has achieved many other accolades, including The Times novel of the year.

Both of these books offer perspectives on motherhood and parenting that are long overdue and both have affected me deeply. Working with people on the transition to parenthood, these books provide a rich resource on the themes of changing identity and how society needs to change to support people on this journey. It is a journey that most of us go through but which many of us are poorly prepared for. That needs to change.

I’ve just finished a lovely little book The Umbrella Mouse by Anna Fargher. When I was browsing in my local bookshop a few months ago, one of the assistants recommended it to me and said it had had her in tears. I knew then it was a ‘must-read’! I got my copy secondhand online and it’s signed!

I’ve just finished a lovely little book The Umbrella Mouse by Anna Fargher. When I was browsing in my local bookshop a few months ago, one of the assistants recommended it to me and said it had had her in tears. I knew then it was a ‘must-read’! I got my copy secondhand online and it’s signed! The centre of the story is the relationship between two women, Bel and Lydia, who meet at a New Year’s party in 1985, when they are both sixth-formers although at different schools in Yorkshire. They are very different people – Lydia is reserved, generally quite sensible, and from a secure and ordinary family. Bel is wilder, her family rather more bohemian and she has a difficult relationship with her parents. Bel grew up in France and then London and it is her father’s job that has brought them to northern England, where she is something of an outsider. Bel and Lydia are drawn to one another, despite their very different personalities; for Lydia, Bel represents spontenaiety, excitement, danger even. For Bel, Lydia represents security, a steady point in a turning world.

The centre of the story is the relationship between two women, Bel and Lydia, who meet at a New Year’s party in 1985, when they are both sixth-formers although at different schools in Yorkshire. They are very different people – Lydia is reserved, generally quite sensible, and from a secure and ordinary family. Bel is wilder, her family rather more bohemian and she has a difficult relationship with her parents. Bel grew up in France and then London and it is her father’s job that has brought them to northern England, where she is something of an outsider. Bel and Lydia are drawn to one another, despite their very different personalities; for Lydia, Bel represents spontenaiety, excitement, danger even. For Bel, Lydia represents security, a steady point in a turning world.

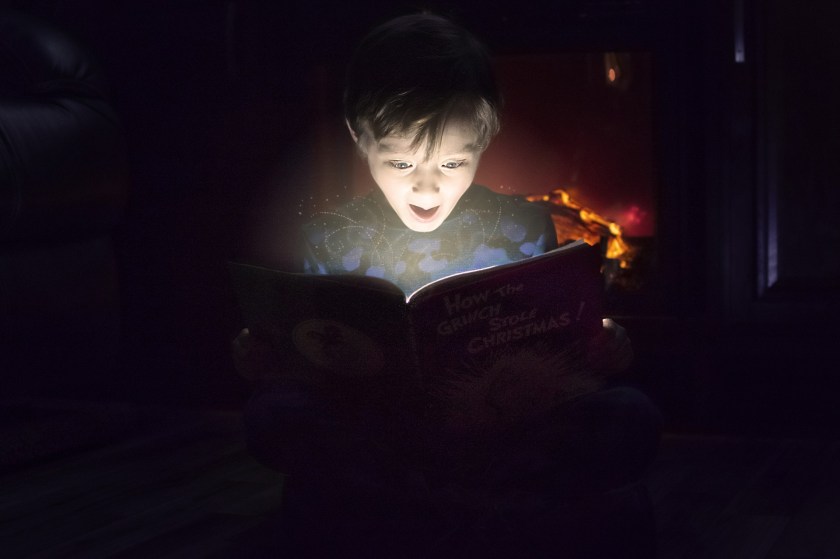

However, with autonomy comes power – if they are having an ‘at home’ day they can simply slip under the radar and spend a great deal of quality time with their phones and tablets (oh for the days when I only worried about how much Balamory they watched!) They can secrete themselves in their bedrooms while I lose myself in all my usual activity. At their age, sure I watched a lot of telly while my parents were out at work in the school holidays, but I also spent plenty of time with my nose in a book. Digital distractions were fewer and less powerful.

However, with autonomy comes power – if they are having an ‘at home’ day they can simply slip under the radar and spend a great deal of quality time with their phones and tablets (oh for the days when I only worried about how much Balamory they watched!) They can secrete themselves in their bedrooms while I lose myself in all my usual activity. At their age, sure I watched a lot of telly while my parents were out at work in the school holidays, but I also spent plenty of time with my nose in a book. Digital distractions were fewer and less powerful.

Just Fly Away is the debut novel from 1980s brat-pack actor, turned award-winning director and author Andrew McCarthy. It tells the story of fifteen year old Lucy who discovers that she has a half-brother, the result of an affair her father had, living in the same town. Like No Filter it is a novel about secrets and lies, as Lucy escapes to Maine to live with her grandfather, himself estranged from the family, and to work through the confusion and torment her discovery has left her with.

Just Fly Away is the debut novel from 1980s brat-pack actor, turned award-winning director and author Andrew McCarthy. It tells the story of fifteen year old Lucy who discovers that she has a half-brother, the result of an affair her father had, living in the same town. Like No Filter it is a novel about secrets and lies, as Lucy escapes to Maine to live with her grandfather, himself estranged from the family, and to work through the confusion and torment her discovery has left her with. Finally, on a different topic, there is All the Things that Could Go Wrong by Stewart Foster which concerns the relationship between two boys, initially at loggerheads, who find common cause when they are forced to spend time together. Alex suffers from OCD and worries about everything. His condition is so severe that he rarely leaves home. Dan is angry, because his older brother Alex has left home and he feels lost. Initially, he takes it out on Alex, whom he perceives as weak and ineffectual, but the boys’ mothers force them together on a garden building project and the understanding that develops between is healing for both.

Finally, on a different topic, there is All the Things that Could Go Wrong by Stewart Foster which concerns the relationship between two boys, initially at loggerheads, who find common cause when they are forced to spend time together. Alex suffers from OCD and worries about everything. His condition is so severe that he rarely leaves home. Dan is angry, because his older brother Alex has left home and he feels lost. Initially, he takes it out on Alex, whom he perceives as weak and ineffectual, but the boys’ mothers force them together on a garden building project and the understanding that develops between is healing for both.