I’ve had another long break from blog posting, but I’m happy to report that I have had a busy month of travelling, some near and some far. It was my middle child’s 21st birthday so we made a short trip to the beautiful city of Cambridge for a family celebration. Hotel accommodation in Cambridge can be pricey and I have found that the cheaper accommodation can be hit and miss and seldom has free parking. So we stayed a little outside town at the wonderful Madingley Hall. It belongs to the University and there seemed to be some conference groups there, although it is a substantial property and was by no means full. It was beautiful, with fabulous grounds and is close to one of the park and ride facilities so I recommend it highly if you are thinking of going there.

A few days after the birthday I set off for Egypt! I always enjoyed travelling when I was younger, but since having my children this has been on the back burner. Our holidays have been family affairs and we have tended to stick to UK and European destinations with the kids. This has also been the first year in about two decades (!) when I have not been bound by school holidays. My husband has a busy work schedule and is less interested in exotic locations than me so I took myself off alone! Well, not exactly alone…I went on a group tour, feeling that perhaps I needed to build my confidence a bit with solo travel before going it completely alone. I could not have made a better decision! I travelled with a company called Intrepid and the tour was fantastic. It was a very international group- Australians, New Zealanders, US, Canadian and Italian citizens and even a couple of other Brits! Such a wonderful and interesting group of people, we bonded really well and I am missing them all so much. Our tour guide was brilliant, so knowledgeable about ancient Egyptian history and culture.

I had the most marvellous time and as soon as I came back I was on Intrepid’s website thinking about my next trip! Some of my fellow travellers went on to Jordan and looking at their Instagram posts I think that might be next on my list. I’ve posted some photos below. Egypt is an incredible country, with beautiful friendly people and I will definitely go back there.

I had a few days to find my feet again and catch up on laundry before I was off again, this time on what has become an annual visit for me – to the Hay Festival. For the past couple of years I have camped at the Tangerine Fields site just outside Hay on Wye, but I decided I am over camping! I stayed in a B&B in Talgarth, about 10 minutes drive from the Festival site.

I was there for three days and, as usual, had a fantastic time. There were two particular highlights for me: my final event on Saturday evening was a talk from Radiohead bass player Colin Greenwood, who has recently published a book of photographs he has taken over the years performing and recording with his band. He was very warm and candid and clearly exhausted having just returned from touring the US with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Despite this he spent almost two hours afterwards signing copies of his book How to Disappear, chatting to fans and having selfies with them – such a pro. My other highlight was seeing Kate Mosse and Jacqueline Wilson, two giants of the literary scene. Apparently, between them, they have sold 50 million books worldwide – staggering. The pair are great friends and talked about their writing habits, their current projects and many other topics. They were both so down to earth and modest.

My other events were Jeremy Bowen, BBC International Editor and often to be found reporting from the Middle East or Ukraine – I have seen him at Hay before. Listening to him is sobering indeed. I saw Hallie Rubenhold, author of best-selling non-fiction book The Five about the women victims of Jack the Ripper. she has just published a book about the case of Dr Crippen and his lover, who murdered Crippen’s first wife. She was very interesting. Less interesting was Jeremy Hunt MP. Politicians are usually good value at Hay, but I’m afraid Mt Hunt had disappointingly little gossip! He has just published a book talking about how Britain can be great again, but it struck me as somewhat blinkered about how we became un-great in the first place. His interviewer Robert Peston was a little more entertaining.

A few photos of my Hay Festival experience below.

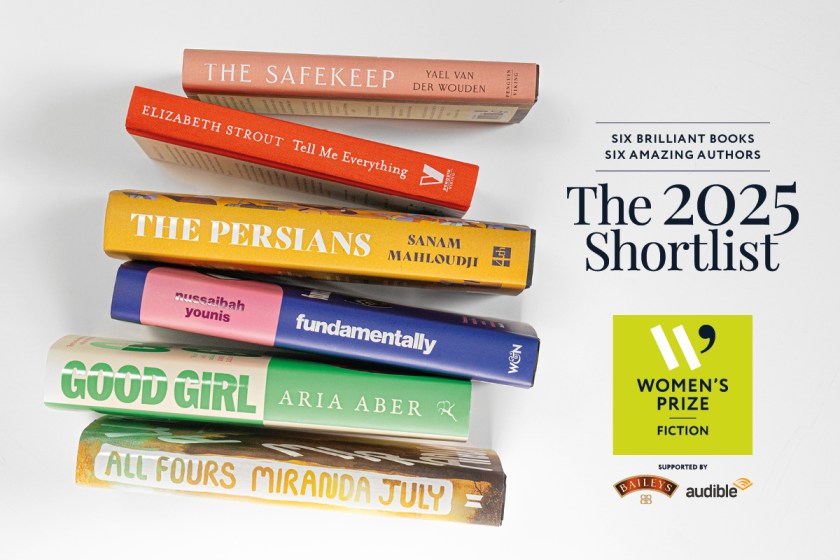

I am looking forward to a bit of staying put in June! The winner of the Women’s Prize will be announced next week (12th June). I have a couple of reviews to post of books on the shortlist that I have read, so will aim to get those out in the next few days.