I could not have been more delighted at the announcement last week that Shuggie Bain, the debut novel by Douglas Stuart (a Scottish fashion designer who now lives in New York city), had won the Booker Prize. I posted last week about how I had enjoyed the book. I did not exactly predict the winner; I’d only read two of the books on the shortlist and the other one I didn’t really like! I felt more a part of the ceremony this year than ever before. It was incorporated into the Radio 4 arts programme Front Row, whereas usually there is a fancy-pants dinner, and Will Gompertz, in his black tie, appears at the end of News at Ten, to tell us, briefly, who has won. The rest of us, the actual real-life readers and book-buyers, are left out of the glittery literati event. Not this time though; sitting at home, like all the nominated authors, I was on tenterhooks too.

It was the same with the Women’s Prize, back in the summer. It was such a treat to attend all the virtual pre-prize interviews, hosted by author Kate Mosse, with the worldwide audience posting their questions and comments on the Zoom rolling chat. We would never have been able to do that before, when such things would all have taken place in London. I hope that is one aspect of life that we keep, going forward. The winner of the Women’s Prize this year was Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell. I had not read at the time it was awarded the prize, but it was on my TBR list. I have subsequently read it and, if you haven’t already heard, it was a joy to read. It is one of the most profoundly moving books I have read in a very long time; Maggie O’Farrell is an author at the top of her game and she is still only 48.

Hamnet is the story of a marriage and a child. The marriage is that between William Shakespeare (though he is never actually named in the novel) and his wife Agnes (we know her better as Anne Hathaway of course, but her birth name was actually Agnes). The novel does not pursue a linear narrative; it begins with the eleven year old boy Hamnet searching frantically for his twin sister Judith, who is dangerously sick with fever. The house belongs to his grandparents, his father’s parents. His father is away working in London and the family has lived with them since his parents married. The grandfather is a glove-maker and both produces and sells his gloves from the home, where there is a window that faces out on to the Stratford street. The grandfather is a violent bully who believes his playwright son is a hapless good-for-nothing.

Hamnet’s mother is older than his father by some seven or eight years, and they married after a brief and passionate courtship which led to Agnes falling pregnant. This was partly the intention; Agnes, whose mother had died when she was a child, is a wildish creature whom her vulgar stepmother treats with suspicion and contempt. For Agnes, the pregnancy is a wish-fulfilment, and the hasty marriage a way out of her father’s home, which is now dominated by his second wife and a new set of offspring.

Agnes gives birth, as she expects, to a girl, Susannah. Agnes has a deep knowledge of plants and herbs and people come to her for healing. She is also said to have powers of premonition. These qualities are said to be inherited from her mother. When she falls pregnant for a second time Agnes is puzzled and distressed as she feels instinctively that something is wrong or that some ill fate awaits the child, but she cannot pinpoint what it is. Her confusion over whether the baby is a boy or girl troubles her. In the end she gives birth to twins, a girl and a boy, and her husband laughs off her confusion.

While the children are growing, the playwright pursues his career and, encouraged, by Agnes, goes to London, ostensibly to sell his father’s gloves, but actually to explore what opportunities there might be for him there. Dazzled by the theatre and by the thespians he meets, he decides that he should stay in order to make enough money to support his family. He does this with his wife’s blessing although she does not realise, at this stage, how far apart the separation will drive them.

SPOILER ALERT…ish (you have probably already have heard what happens):

Back in Stratford, Judith contracts the plague and becomes dangerously ill. Agnes believes her child will die. There is a shocking turn of events, however, when Judith suddenly recovers, but, exhausted by the sleepless worry and the caring for her daughter, Agnes fails to notice the rapid deterioration in her son Hamnet, who suddenly contracts the disease. It is a brilliant and devastating few pages as we regain Judith and lose Hamnet. O’Farrell has said that she could not write this scene until her own son had passed the age of eleven. It seems it was as profound an experience writing it as it is to read.

Hamnet’s father does not make it back in time for his son’s last breath and this sets the tone of the remainder of the book. Hamnet’s death occurs about halfway through and the rest of the novel explores the grief experienced by husband and wife. Each feels their loss in a different way and their inability to find comfort in each other in such a terrible moment almost breaks them, both as a couple and as separate individuals.

The ending of the book is interesting, I won’t explain how it pans out, except to say that the playwright writes a play called Hamlet in which a young man dies, but, for me, the emotional peak is much earlier on with Hamnet’s death. The rest is a fascinating study of grief but not as intense.

A wonderful book, brilliantly conceived, brilliantly executed. A worthy winner, despite being up against the very brilliant The Mirror and the Light by Hilary Mantel. I think it’s more accessible and a little more human than Mantel’s book, which I also loved, by the way.

Very highly recommended.

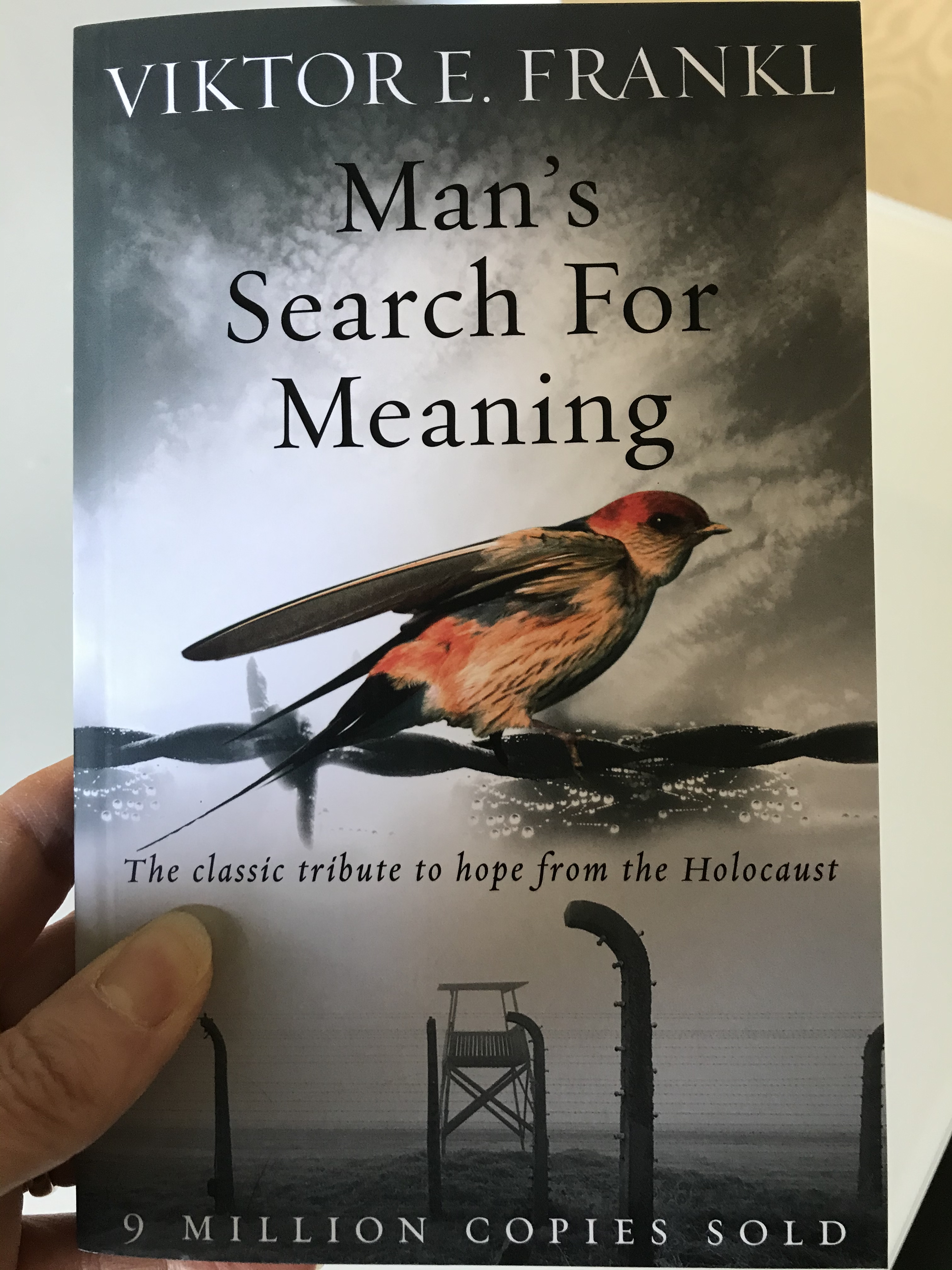

Viktor E Frankl was a psychiatrist who is credited with developing one of the most important theories in the field human psychology (logotherapy) since Freud. He was developing his theory before he was captured by the Nazis but his time in the concentration camp enabled him to observe human beings in extreme conditions and further evolve his ideas.

Viktor E Frankl was a psychiatrist who is credited with developing one of the most important theories in the field human psychology (logotherapy) since Freud. He was developing his theory before he was captured by the Nazis but his time in the concentration camp enabled him to observe human beings in extreme conditions and further evolve his ideas.

The book incorporates cognitive behavioural therapy techniques into exercises for addressing, for example tendencies to be self-critical. Low self-esteem can lead to debilitating inhibition, irrational fears, in both social and professional situations, and, I believe, can truly limit one’s life experience, achievement, enjoyment in life and personal relationships. I have found it really tough working through this book, particularly the chapters which focus on understanding the causes of poor self-esteem. Thinking about my relationship with my parents, in the aftermath of my mother’s death just a few months ago has not been easy.

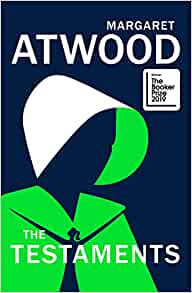

The book incorporates cognitive behavioural therapy techniques into exercises for addressing, for example tendencies to be self-critical. Low self-esteem can lead to debilitating inhibition, irrational fears, in both social and professional situations, and, I believe, can truly limit one’s life experience, achievement, enjoyment in life and personal relationships. I have found it really tough working through this book, particularly the chapters which focus on understanding the causes of poor self-esteem. Thinking about my relationship with my parents, in the aftermath of my mother’s death just a few months ago has not been easy. It is truly a groundbreaking novel, but curiously, in my view, less in its own right than as an extension, a continuation of, the work started with the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. What is also partly so extraordinary about The Testaments is how relevant its story remains over thirty years on from The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of equality legislation, human rights legislation, more women in positions of power and authority, we still have world leaders able to express their misogyny openly and with impunity, and violence against women and girls seems as rife as ever. Atwood is Canadian, but her novel is a dystopian vision set in the United States, where, in the last year, we have seen the erosion of women’s reproductive and therefore health rights in some states and the substantial threat of more to come. This novel seems so urgent and necessary.

It is truly a groundbreaking novel, but curiously, in my view, less in its own right than as an extension, a continuation of, the work started with the publication of The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985. What is also partly so extraordinary about The Testaments is how relevant its story remains over thirty years on from The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of equality legislation, human rights legislation, more women in positions of power and authority, we still have world leaders able to express their misogyny openly and with impunity, and violence against women and girls seems as rife as ever. Atwood is Canadian, but her novel is a dystopian vision set in the United States, where, in the last year, we have seen the erosion of women’s reproductive and therefore health rights in some states and the substantial threat of more to come. This novel seems so urgent and necessary.

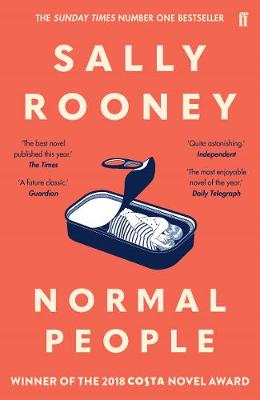

It seems appropriate that I should be posting a review of Normal People this week, a book so very much about Ireland, the challenges and contradictions at the heart of a nation that has transformed itself in recent years. It is not just about Ireland, but about what it means to be young in Ireland and about class. It is also about identity and, in common with some of the issues faced in the UK and many other societies I am sure, the draw away from regional towns and cities, towards a centre, a capital, where there is perceived to be more opportunity, and what that means both for the individual and for society in the wider sense.

It seems appropriate that I should be posting a review of Normal People this week, a book so very much about Ireland, the challenges and contradictions at the heart of a nation that has transformed itself in recent years. It is not just about Ireland, but about what it means to be young in Ireland and about class. It is also about identity and, in common with some of the issues faced in the UK and many other societies I am sure, the draw away from regional towns and cities, towards a centre, a capital, where there is perceived to be more opportunity, and what that means both for the individual and for society in the wider sense. I have chosen a book which caught my eye a couple of months ago – The Lido by Libby Page. It concerns a friendship between two women, 86 year-old widow Rosemary and 26 year-old Kate, who strike up a bond when their local outdoor swimming pool in Brixton, south London, is threatened with closure. The two women have different reasons for wanting to campaign to keep the lido open, but they are brought together in a common cause.

I have chosen a book which caught my eye a couple of months ago – The Lido by Libby Page. It concerns a friendship between two women, 86 year-old widow Rosemary and 26 year-old Kate, who strike up a bond when their local outdoor swimming pool in Brixton, south London, is threatened with closure. The two women have different reasons for wanting to campaign to keep the lido open, but they are brought together in a common cause.

Milton the Mighty by Emma Read

Milton the Mighty by Emma Read

The Dog Who Saved the World by Ross Welford

The Dog Who Saved the World by Ross Welford

Meat Market by Juno Dawson

Meat Market by Juno Dawson On The Come Up by Angie Thomas

On The Come Up by Angie Thomas