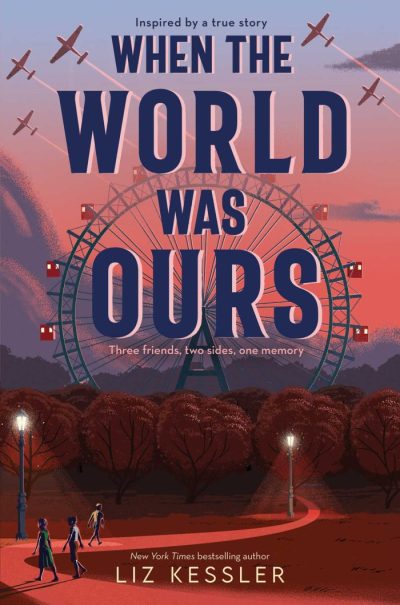

I read this book at the end of the summer. It is set partly in Vienna, where we went for our family holiday in July, though that is not why I read the book, or why I went to Austria! Pure coincidence. When the World Was Ours is actually a book for young people, or what is often called ‘middle grade’ fiction, but that should not deter any adult from buying it – I was gripped from start to finish and absolutely loved it.

The book opens in Vienna in the mid-1930s at the birthday celebration of nine year-old Leo. Leo’s father has taken him to the city’s ferris wheel for a treat, along with Leo’s two very close friends Max and Elsa. There they meet an English couple, a dentist and his wife, who are in town for a conference and afterwards the couple and all the children are invited back to Leo’s family home for Sachertorte, the iconic Austrian dessert.

The three children are inseparable, firm friends; Elsa’s main dilemma is which of the two boys she will marry when they grow up! But timing is everything, and as political events around the children develop, it is clear that they will not be unaffected by the fascist takeover of the city and country by Hitler and his army. Leo is Jewish, as is Elsa. Max is not. This will create a wedge between them as Leo and Elsa’s families must navigate the new environment; should they stay or should they try and escape? Meanwhile, for Max, the challenge is rather different. Always a more timid boy, somewhat in Leo’s shadow, he finds there are expectations upon him once his father begins to rise up the Nazi ranks, which it is not clear he will be able to meet.

I do not want to say more about the plot of the novel as it is a critical part of the enjoyment of the book. There is a gloomy inevitability about many of the events, however, as you might expect. It is a compelling read, with chapters alternating between the perspectives of each of the children.

The characters are well-drawn and the writing has a graceful simplicity that suits the subject-matter, the primary intended audience and the gravity of the events. It is plain without being patronising and I felt it was an authentic portrayal of the voices of the individual children.

I had the great pleasure to meet the author and discuss the book with her as she lives in the north west of England, not far from me. She came to our book club and was very generous with her time and her thoughts. As is stated at the beginning of the book, there are autobiographical elements as it is based on her own family history. This adds even more poignancy to the story and is a timely reminder that fascism and authoritarianism must never again be allowed to take hold. The consequences are intolerable.

Vienna

It was by sheer coincidence that my family went on holiday to Austria this summer. We have been skiing there a number of times in the last couple of decades, but it is many years since I have been there in the summer. We spent a few days in Vienna and then travelled west to Schladming, normally a ski resort but a walker’s paradise in the summer, and where the hills were most definitely alive – verdant, green, lush and beautiful.

Before I went I looked up ‘famous Austrian writers’ because I found I could not think of any! The list did not include many that I had heard of apart from Arthur Schnitzler, who wrote the novella Eyes Wide Shut, famously adapted for the screen by Stanley Kubrick and starring Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise, and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Austrian culture is perhaps better distinguished by its eminent composers and artists, such as Mozart, Schubert, Strauss, Haydn and Klimt.

Vienna is truly one of the must-see capitals of Europe, however, not least because of its historical significance and its closeness to eastern Europe; Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, is less than one hour’s drive away and the mighty Danube runs through both cities. Vienna is a stunning city, beauty on every corner, and it even gives its name to a particular kind of patisserie – Viennoiserie! Needless to say we sampled much of what it had to offer on this front, frequenting many coffee houses, including the famous Cafe Central, where Sigmund Freud is said to have hung out, and the Hotel Sacher, which claims the Sachertorte as its own.

Had I read When the World Was Ours before going to Vienna, I would certainly have headed for the vast green space to the east of the city where the Riesenrad, the giant ferris wheel, still stands – next time!