I’m going a bit highbrow this week – any lawyers in the room? I’m not a big reader of non-fiction, so a few months ago I set myself the task of reading a couple of books from the shortlist of the Baillie Gifford Prize, one of the most prestigious non-fiction awards in the world. I read Negroland by Margo Jefferson, which I really enjoyed and reviewed here back in February. East West Street actually won the prize; I enjoyed this a little less than Negroland, I have to say, but it is a remarkable work and it wasn’t what I was expecting.

These days we take for granted the terms ‘genocide’ and ‘crimes against humanity’; they are used fairly frequently, especially since the Balkan war in the 1990s, and fairly interchangeably, it seems to me. But did you know that these were only established as legal terms at the Nuremberg trials after the Second World War? The gravity and scale of the crimes committed by the Nazis is largely undisputed, but when it came to actually bringing individuals to justice at the court of law in Nuremberg in the post-war atmosphere, charges had to be specified and evidence had to be considered. In many ways, it seems to me, it was a piece of theatre, but the legal minds at the time were severely exercised. And I guess if you are on the winning side, both militarily and morally, the pressure to maintain the moral high-ground is immense. The victors had to be seen to be following a path of rectitude and adherence to international standards of law.

“Jackson [presiding judge at the Nuremberg trial] crafted each word with care, signalling its significance. He spoke of the victors’ generosity and the responsibility of the vanquished, of the calculated, malignant, devastating wrongs that were to be condemned and punished. Civilization would not tolerate their being ignored, and they must not be repeated. ‘That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengenace and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgement of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to reason.'”

(p.288, quote from Judge Robert H. Jackson, opening the Nuremberg trial)

This book provides a historical account of the intellectual tussle between two of the finest legal minds of the time: Hersch Lauterpacht and Rafael Lemkin. Lauterpacht fought for the term ‘crimes against humanity’ whereas Lemkin wanted ‘genocide’. To most of us the differences between the two might seem inconsequential, but the differences are in fact, as is discussed in the book, fundamental to the basis of international law. This is not the place for me to rehearse the arguments (even if I could!). I did struggle with the legal minutiae of the book, though I was able to grasp the broad concepts and it certainly made me think about an issue which I can honestly say I have never thought about before. And it was interesting, honestly!

So far I have probably made the book seem dry and dull to the average reader (though perhaps sexy to any of you legal eagles!), but prizes are not won by being dry and uninteresting and the author is far more successful than that; by far the more engaging aspects of this book are the human stories. East West Street is a thoroughfare in the city of Lviv, in modern day Ukraine, but which has previously been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and of Poland. It is also a town with which both Lauterpacht and Lemkin were linked. Lviv plays a central role in the book because it provides a snapshot of the Nazis’ ambitions and methods.

The heart of this book, however, is the author’s own quest to find out about his grandparents, Leon and Malke Buchholz, a young Jewish couple from Lviv who were forced to leave their home with their baby daughter Ruth, the author’s mother. Leon and Malke have revealed little about their early life and the author has many unanswered questions. Now dead, he sets about researching his grandfather’s early life, the circumstances of his marriage and how it was he came to be in England with Malke and Ruth. The author becomes a detective investigating his own family history and confronts some difficult truths, as is often the case. He conducts this search alongside his research into the legal basis of the Nuremberg trials and finds links and parallels.

The book is broken up into distinct parts: for example, the opening chapter is about Leon and his early life and then there are similar chapters on Lauterpacht and Lemkin. These were the chapters I found most engaging and most moving. Towards the end is a very long chapter about Nuremberg itself which was fascinating as it was not something I knew very much about before. Some parts of the book were for me overly detailed and I skimmed through some of these.

Unquestionably, however, there lies at the heart of this book a deep and terrible tragedy about which it is always worth being reminded: how prejudice, ideology, lies and propaganda, stupefied a nation, and, combined with power and determination, saw the murder of millions of people and displaced or traumatised many millions more and the consequences are still being felt down the generations today.

This is a powerful book which I recommend if you have an interest in history or the law, or if you just like to read about uncovering family stories. It looks daunting but it’s actually a quicker read than you might think.

Have you read any non-fiction books that recently that you recommend?

If you have enjoyed this post and would like to follow my blog please subscribe by clicking on the button below or to the right, depending on your device.

What is so immediately intriguing about the title of the novel, of course, is that Holland is very, very flat. But In the Dutch Mountains imagines a world where the Netherlands extends much further south of its modern borders to northern Spain and the Pyrenees (hence the Dutch mountains). The narrator is himself a Spaniard, a civil servant who not only relates the story, but also philosophises on the processes of writing and story-telling: a story within a story. The main characters in the tale are Kai and Lucia, a slightly other-worldly circus couple, remarkable for their physical perfection, who are relieved of their jobs (because times have moved on and audience tastes have changed) and find themsleves travelling south to look for work. Kai is kidnapped and Lucia sets out on a journey to find him, accompanied by an old woman she meets on the way who agrees to drive her to find her lover.

What is so immediately intriguing about the title of the novel, of course, is that Holland is very, very flat. But In the Dutch Mountains imagines a world where the Netherlands extends much further south of its modern borders to northern Spain and the Pyrenees (hence the Dutch mountains). The narrator is himself a Spaniard, a civil servant who not only relates the story, but also philosophises on the processes of writing and story-telling: a story within a story. The main characters in the tale are Kai and Lucia, a slightly other-worldly circus couple, remarkable for their physical perfection, who are relieved of their jobs (because times have moved on and audience tastes have changed) and find themsleves travelling south to look for work. Kai is kidnapped and Lucia sets out on a journey to find him, accompanied by an old woman she meets on the way who agrees to drive her to find her lover. I’m off on a short holiday to the Netherlands so I’m planning to take some reading with me, of course, and have decided on another book from my

I’m off on a short holiday to the Netherlands so I’m planning to take some reading with me, of course, and have decided on another book from my  Nina is twenty when we meet her in the early 1980s. She lives with Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the London Review of Books, and her two young sons, Sam and Will, to whom she is a nanny. They live at 55 Gloucester Crescent NW1, an area that was also home to other literary types, among them Alan Bennett and Claire Tomalin, who also make appearances in the book, particularly ‘AB’ who is a great friend of ‘MK’.

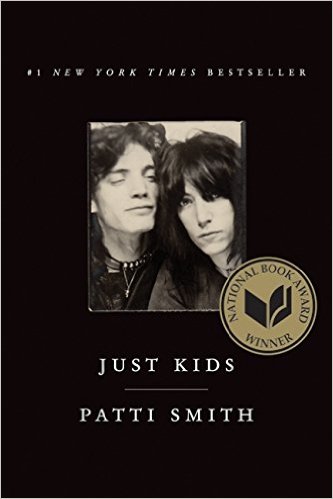

Nina is twenty when we meet her in the early 1980s. She lives with Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the London Review of Books, and her two young sons, Sam and Will, to whom she is a nanny. They live at 55 Gloucester Crescent NW1, an area that was also home to other literary types, among them Alan Bennett and Claire Tomalin, who also make appearances in the book, particularly ‘AB’ who is a great friend of ‘MK’. So, it gives me great pleasure to announce that I completed the March challenge and the pile is one volume smaller. I really enjoyed Just Kids and I’m pleased I finally got around to it. I’ve also given up book-buying for Lent so hopefully I will be better able to resist temptation in the future and tackle the unread books before buying new ones. Sometimes.

So, it gives me great pleasure to announce that I completed the March challenge and the pile is one volume smaller. I really enjoyed Just Kids and I’m pleased I finally got around to it. I’ve also given up book-buying for Lent so hopefully I will be better able to resist temptation in the future and tackle the unread books before buying new ones. Sometimes. I am fortunate to live in Manchester, northern England, the setting of this book. It’s also where Gaskell spent much of her early life. You can visit

I am fortunate to live in Manchester, northern England, the setting of this book. It’s also where Gaskell spent much of her early life. You can visit  I’ve been an admirer of Patti Smith for a number of years now. I’m a bit young to have been a fan of hers when she first broke onto the music scene in the mid-1970s. I became aware of her much later when I picked up a sale copy of her debut album Horses. I was also aware of Robert Mapplethorpe, the late artist-photographer who was her lover and then close friend when they were both very young. Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989 and it must have been in the 1990s that I saw an exhibition of his work in London (I had an interest in photography at the time). Later on again I learned about the connection between the two and how Patti had been, if you like, Mapplethorpe’s ‘muse’ when he was first discovering his art.

I’ve been an admirer of Patti Smith for a number of years now. I’m a bit young to have been a fan of hers when she first broke onto the music scene in the mid-1970s. I became aware of her much later when I picked up a sale copy of her debut album Horses. I was also aware of Robert Mapplethorpe, the late artist-photographer who was her lover and then close friend when they were both very young. Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989 and it must have been in the 1990s that I saw an exhibition of his work in London (I had an interest in photography at the time). Later on again I learned about the connection between the two and how Patti had been, if you like, Mapplethorpe’s ‘muse’ when he was first discovering his art. Regular visitors to this blog will know that I am passionate about children’s literature. My children are part of the generation that grew up with Harry Potter. JK Rowling is one of my heroes, for a number of reasons, but primarily for all that she has done to get (and keep) children reading, particularly those who might otherwise not have done so. Harry Potter wasn’t the first literary character to bring wizarding and magic into children’s literary lives, however. The Snow Spider was first published 30 years ago and was a multiple award winner. It was originally published as a trilogy, but this anniversary volume has been issued as a stand-alone. I chose it for the book club I run at my daughter’s primary school.

Regular visitors to this blog will know that I am passionate about children’s literature. My children are part of the generation that grew up with Harry Potter. JK Rowling is one of my heroes, for a number of reasons, but primarily for all that she has done to get (and keep) children reading, particularly those who might otherwise not have done so. Harry Potter wasn’t the first literary character to bring wizarding and magic into children’s literary lives, however. The Snow Spider was first published 30 years ago and was a multiple award winner. It was originally published as a trilogy, but this anniversary volume has been issued as a stand-alone. I chose it for the book club I run at my daughter’s primary school.