‘May you live in interesting times’ is an English expression which is said to be translated from an ancient Chinese curse. Laced with irony, it conveys the danger and the associated anxiety when national or international events seem to go through periods of intense change or activity. I don’t know about you, but it certainly feels to me that we are living in interesting times at the moment! It’s not so much the political turmoil (British, European, global) that bothers me, I suspect every generation experiences times when world events seem dangerously unpredictable. No, it’s more the way that power is exercised by a small group over a large group and how the small group gets the large group to behave in particular ways that benefit the small group. I’m talking about lying with impunity, inequality and abuse, distorting evidence (especially about climate change) and stirring up hatred. These things frighten me more and have the potential to damage more of us than the ‘threats’ others would have us fear, for example, North Korea, terrorism or immigration.

In recent weeks I have turned to two very important books which have sharpened my understanding of our present situation. Whilst on holiday in the Summer I read A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess, and I have been listening to 1984 by George Orwell, a book that I last read whilst at University.

I read A Clockwork Orange on my husband’s recommendation, straight after he’d completed it – it’s one of his favourite films, which we have watched many times, but neither of us had read the book. It’s quite short, but also quite hard-going as it is narrated by the central character, Alex, who speaks in ‘nadsat’ a kind of teenage vocabulary of the future, based loosely on Slav languages. I read it with a glossary (though Burgess intended that it should not be), but after while I found I did not consult it, and it flowed better just to read it and understand the sense, if not every word.

I read A Clockwork Orange on my husband’s recommendation, straight after he’d completed it – it’s one of his favourite films, which we have watched many times, but neither of us had read the book. It’s quite short, but also quite hard-going as it is narrated by the central character, Alex, who speaks in ‘nadsat’ a kind of teenage vocabulary of the future, based loosely on Slav languages. I read it with a glossary (though Burgess intended that it should not be), but after while I found I did not consult it, and it flowed better just to read it and understand the sense, if not every word.

It is a book about violence and hatred, between generations, between genders, between different social groups. It is also about social isolation, about fractured communities and about a violent experimental penal system where punishment is presented by the author as nearly as vile as the original offence. Parts of it are difficult to read because of the violence (there is a terrible rape scene at the beginning when Alex and his ‘droogies’ (friends) go on a drink and drug-fuelled rampage through the town), but mostly because it is profoundly disturbing as an example of how a society, or parts of society, can be persuaded to act in the most vicious ways, and how this is driven by collective approval, the power of the group. It is a book about collective moral failure and the breakdown of the social contract which maintains order.

I listened to 1984 on audiobook over a period of several weeks in my car. There were moments when I had to pull over, aghast at what I was hearing. It was written in 1949 and I first read it lazily and only partially in the late ’80s, when I was 19 or 20. At that time the book was only 40 years old, and it was amusing that it described a future society in a year that had already passed (just as Space:1999 became ironic at the start of the 21st century!) The book is now over 70 years old and, frankly, parts of it could describe the world we live in today, our ‘interesting times’. The book describes a totalitarian state, Oceania, said to be based on Stalinist Russia, led by an omnipotent strongman Big Brother. The world is divided into three power blocs – in addition to Oceania there is Eurasia and Eastasia – who are perpetually at war. The constant state of war justifies the indefinite suspension of human liberties and the permanent control not only of human action, but of human thought. Offenders are eliminated, cruelly, and power is exercised through fear.

In the context of our own ‘interesting times’ the themes which disturbed me most were, firstly, the ‘cult of personality’ – Big Brother is all powerful and his power is conferred by an artificially inspired devotion. I’ve decided you can have too much personality in a leader and it is overrated. Secondly, ‘historical revisionism’ – populations are manipulated all the time by being told subjective versions of events, both past and present, that suit the teller and are politically expedient. Extremists and the seemingly not-so extreme, are guilty of this, it seems to me. And finally, “2+2=5” – we all believe we think for ourselves, but human beings can be persuaded to think the unthinkable, or believe what is objectively untrue. From big business marketing (corporations who deliberately befuddle our notions of ‘want’ and ‘need’) to political spin (like the numbers attending a political rally, or how happy they are to be there) to selling whole populations a pup, it seems they will dare to persuade us of anything. I fear 1984 could be renamed The 20-teens.

Do you think we are living in ‘interesting times’?

If you have enjoyed this post, do follow my blog and connect with me on social media.

The cover is lovely and there are a handful of illustrations in the book which are truly beautiful and very evocative. The apparent subject matter (animals) and the fact that it has some illustrations might put off some of the target readership (10-11 year olds, I would say), particularly the more advanced readers among them, who might think it is better suited to younger ones. The themes, however, are much more mature than you might think and may in fact be upsetting to more sensitive 9-10 year olds, say. It is perfect, therefore, for older primary school kids who are perhaps more reluctant readers who may find some of those thick volumes a bit daunting. At 276 pages, with a few pictures and nicely spaced typeface, this is a book where pages will be turned quite quickly; in my experience, this is a surprisingly important factor in many children’s enjoyment of a book!

The cover is lovely and there are a handful of illustrations in the book which are truly beautiful and very evocative. The apparent subject matter (animals) and the fact that it has some illustrations might put off some of the target readership (10-11 year olds, I would say), particularly the more advanced readers among them, who might think it is better suited to younger ones. The themes, however, are much more mature than you might think and may in fact be upsetting to more sensitive 9-10 year olds, say. It is perfect, therefore, for older primary school kids who are perhaps more reluctant readers who may find some of those thick volumes a bit daunting. At 276 pages, with a few pictures and nicely spaced typeface, this is a book where pages will be turned quite quickly; in my experience, this is a surprisingly important factor in many children’s enjoyment of a book!

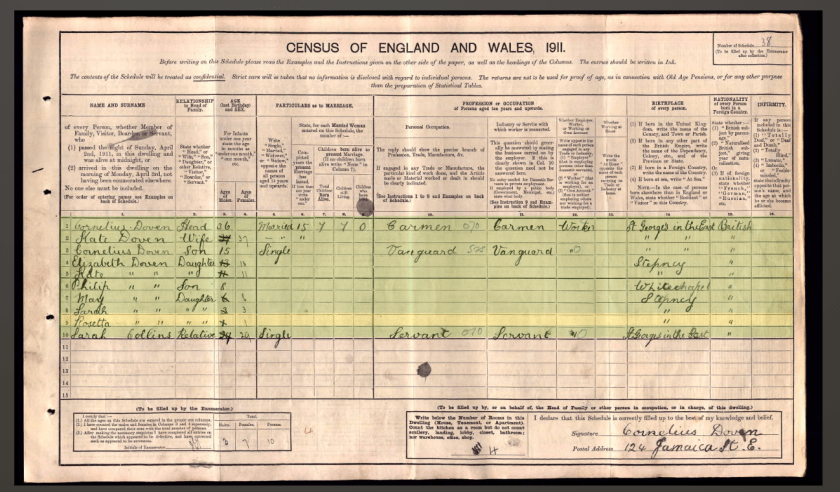

I have been reading a lot of fictionalised biography to help me and one book I read recently I found profoundly moving. Your Father’s Room by French writer Michel Deon is part fiction, part memoir, and looks back to 1920s Paris and Monte Carlo. Edouard, or Teddy, is the only child of a civil servant and his socialite wife. The family moves to Monte Carlo with the father’s job and there is a fascinating insight to life in the south of France at that time, the characters connected to the family and the nature of the relationship between Teddy’s parents. If this is an account in part of the author’s childhood then much of Teddy’s observations will have been imagined by Deon. Perhaps like me he is taking fragments of memory, partial facts and knitting them together to tell a story. It is very engaging even though it is not clear what is truth and what is fiction. How much of any of our family history is a story anyway, ‘facts’ that have been embellished (or concealed) over the years?

I have been reading a lot of fictionalised biography to help me and one book I read recently I found profoundly moving. Your Father’s Room by French writer Michel Deon is part fiction, part memoir, and looks back to 1920s Paris and Monte Carlo. Edouard, or Teddy, is the only child of a civil servant and his socialite wife. The family moves to Monte Carlo with the father’s job and there is a fascinating insight to life in the south of France at that time, the characters connected to the family and the nature of the relationship between Teddy’s parents. If this is an account in part of the author’s childhood then much of Teddy’s observations will have been imagined by Deon. Perhaps like me he is taking fragments of memory, partial facts and knitting them together to tell a story. It is very engaging even though it is not clear what is truth and what is fiction. How much of any of our family history is a story anyway, ‘facts’ that have been embellished (or concealed) over the years? It’s a tough one to review without giving too much away, and the comments on the jacket don’t say very much about the story either, only that it is “exquisite”, “compelling” and “forcefully moving”. The central character is Linda (also Madeline or Mattie to her parents), who is an only child living with her parents in small town Minnesota. To say they live in a rural environment is an under-statement; they live in a cabin in the woods, which they seem to have built themselves, with their dogs. It seems they were formerly part of a small commune, but the other residents have gradually moved away as the cooperative spirit broke down. Linda’s parents are rather remote and she is allowed to roam the area freely, to canoe on the lake as and when she pleases, and to walk many miles in all weathers.

It’s a tough one to review without giving too much away, and the comments on the jacket don’t say very much about the story either, only that it is “exquisite”, “compelling” and “forcefully moving”. The central character is Linda (also Madeline or Mattie to her parents), who is an only child living with her parents in small town Minnesota. To say they live in a rural environment is an under-statement; they live in a cabin in the woods, which they seem to have built themselves, with their dogs. It seems they were formerly part of a small commune, but the other residents have gradually moved away as the cooperative spirit broke down. Linda’s parents are rather remote and she is allowed to roam the area freely, to canoe on the lake as and when she pleases, and to walk many miles in all weathers.

There are a couple of titles that have been on my reading list for a while. The first is Scottish actor and comedian Alan Cumming’s Not My Father’s Son, which was published in 2014. It is linked to his appearance in BBC TV show Who Do You Think You Are? in 2010 in which the result of his research caused him to reflect on his family, his upbringing and, in particular, his relationship with an abusive father. It has received glowing reviews and has also won prizes. The theme of secrets and family research is close to the book I am writing myself so it could be helpful. Or it may just make me feel like givng up now!!!

There are a couple of titles that have been on my reading list for a while. The first is Scottish actor and comedian Alan Cumming’s Not My Father’s Son, which was published in 2014. It is linked to his appearance in BBC TV show Who Do You Think You Are? in 2010 in which the result of his research caused him to reflect on his family, his upbringing and, in particular, his relationship with an abusive father. It has received glowing reviews and has also won prizes. The theme of secrets and family research is close to the book I am writing myself so it could be helpful. Or it may just make me feel like givng up now!!!

Finally, I saw in the bookshop recently that Claire Tomalin has written A Life of My Own, where, for a change, she is writing about herself. I admire Claire Tomalin hugely; she has written some of the finest biographies produced in recent years, covering subjects such as Jane Austen, Samuel Pepys and Mary Wollstonecraft. She has led the most astonishing life: an unhappy childhood, four children, the death of her husband, the loss of a child, and the eternal struggle between motherhood and work. I think I would find this book truly inspiring.

Finally, I saw in the bookshop recently that Claire Tomalin has written A Life of My Own, where, for a change, she is writing about herself. I admire Claire Tomalin hugely; she has written some of the finest biographies produced in recent years, covering subjects such as Jane Austen, Samuel Pepys and Mary Wollstonecraft. She has led the most astonishing life: an unhappy childhood, four children, the death of her husband, the loss of a child, and the eternal struggle between motherhood and work. I think I would find this book truly inspiring.

The narrator and central character is Daniel, who lives with his father (always “Daddy”) and his sister Cathy (a nod to Wuthering Heights, I wonder?) somewhat on the margins of society. Initially, they live with Granny Morley somewhere in the north east, and seem to attend school regularry, though not particularly successfully; it is clear they are ‘different’ and considered outsiders, rather akin to travellers. Cathy and Daniel’s mother has been mostly absent, seemingly a troubled soul with mental health problems and probably addiction, but who then disappears completely, assumed dead. Daddy is a more reliable carer, though he too is frequently absent as he tours the country competing in illegal boxing bouts. He is at the top of his game, however, unvanquished wherever he goes, and seems to make enough of a living from this activity, as well as making plenty of money for those with sufficient funds to gamble heavily on his success.

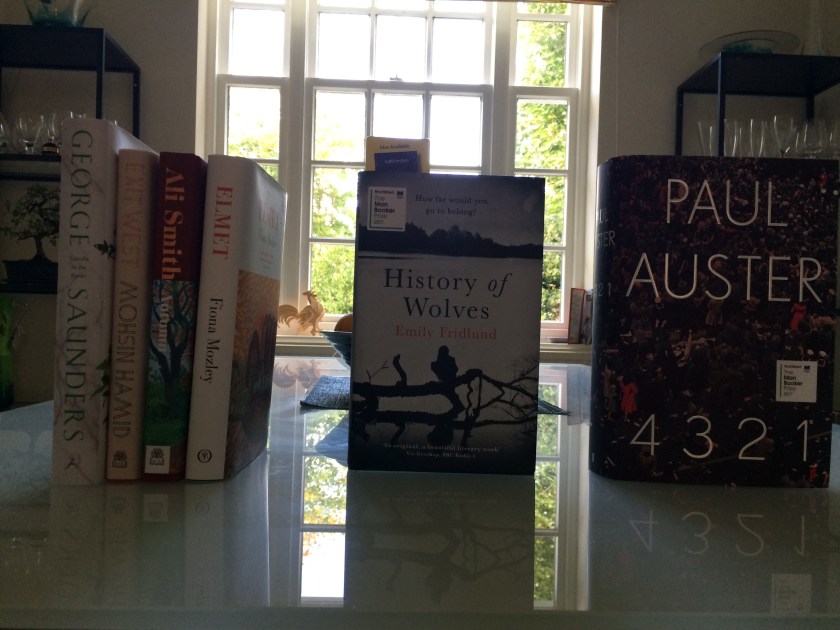

The narrator and central character is Daniel, who lives with his father (always “Daddy”) and his sister Cathy (a nod to Wuthering Heights, I wonder?) somewhat on the margins of society. Initially, they live with Granny Morley somewhere in the north east, and seem to attend school regularry, though not particularly successfully; it is clear they are ‘different’ and considered outsiders, rather akin to travellers. Cathy and Daniel’s mother has been mostly absent, seemingly a troubled soul with mental health problems and probably addiction, but who then disappears completely, assumed dead. Daddy is a more reliable carer, though he too is frequently absent as he tours the country competing in illegal boxing bouts. He is at the top of his game, however, unvanquished wherever he goes, and seems to make enough of a living from this activity, as well as making plenty of money for those with sufficient funds to gamble heavily on his success.  Ali Smith has said that she wrote this book very quickly in the aftermath of the EU referendum in the UK last year. As UK citizens will all understand by now, as we continue to reflect upon/reel over the events of Summer 2016, the outcome of that vote was about so much more than should Britain remain in or leave the European Union. That our social, cultural and political path in this country could be determined by a simple yes or no answer to that question now looks absurd. The election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency in November last year was another cataclysmic event, which provides the context to this novel. Ali Smith has, I believe, outside this book, nailed her political colours fairly firmly to the mast. (I’m not going to do that.) But what we are seeing now, I believe, is the response of artists and writers to the shock of last year’s events, and Autumn is for me, my first foray into a literary reflection.

Ali Smith has said that she wrote this book very quickly in the aftermath of the EU referendum in the UK last year. As UK citizens will all understand by now, as we continue to reflect upon/reel over the events of Summer 2016, the outcome of that vote was about so much more than should Britain remain in or leave the European Union. That our social, cultural and political path in this country could be determined by a simple yes or no answer to that question now looks absurd. The election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency in November last year was another cataclysmic event, which provides the context to this novel. Ali Smith has, I believe, outside this book, nailed her political colours fairly firmly to the mast. (I’m not going to do that.) But what we are seeing now, I believe, is the response of artists and writers to the shock of last year’s events, and Autumn is for me, my first foray into a literary reflection.