Here in the UK, the government announced last week a so-called ‘roadmap’ out of the Covid restrictions. They are emphasising the need to be guided by ‘data not dates’ so nothing is guaranteed of course. Like most people, I am looking forward to being able to see family and friends again; my own parents are both dead, but I have some elderly aunts and uncles I am anxious to visit, and my in-laws are in Dublin and we have not seen them for fourteen months. I am well aware that there is always someone worse off, and I am so sorry for all those who have lost loved ones in this pandemic, in so many cases, without having had the chance to say goodbye.

Yes, like many, I am looking forward to booking a holiday, but it’s actually the smaller things I miss more: seeing friends, going to the cinema or an art gallery, a concert or a play. I want to eat in a restaurant again, cheek by jowl with other diners, and go shopping without a mask. I want to get in the car and drive to the coast for the day, or walk up a mountain, or visit my son at university. I would even be happy providing a taxi service to my daughters, ferrying them around to meet their friends. I want to get on the tram and go into town, or go for a swim or browse in a bookshop or the library. All those things I took for granted and sometimes sighed at having to do. I want them all back.

But there is a prevailing narrative that I feel I must challenge; my daughters will return to school sometime after the 8th of March (when the Department for Education gets around to clarifying how schools should implement rapid Covid testing). Yes, they need to get back, see their friends and be in a classroom again, but they are apprehensive. Working from home has been quite good for them – they do not have to contend with the naughty and disruptive kids. We seem to have forgotten that these things cause anxiety in normal times and that some children get bullied or suffer in a crowded classroom or playground. This is going to be worse when they all return, because so many children will have forgotten how to behave in the classroom and I feel for teachers having to manage discipline once again.

And I am a bit sick of hearing people on television, radio and my neighbourhood telling us how bored we all are and how they have been forced to take up macrame, or whatever. To those people I say, try home-schooling, or working from the kitchen table! I never seem to have the time to be bored! I am rushing around less, that is true, and I will miss this pace of life actually. I know that once restrictions lift life will speed up again.

I will also miss the time that we are sharing as a family – we watch films together, play board games, go out for a walk together every Sunday, and my husband, who used to be away several nights a month for work, has been home all the time. Everyone has time to cook, bake, chat, run, walk, and play. We have grown closer as a family and there is less pressure in life, having to be somewhere by a certain time for a given activity.

I will miss barely using my car. My car is quite old and for a while there I fancied something newer, less scratched, that didn’t scream ‘Mum’. Now I don’t care. It’s been weeks since I put fuel in it and that feels great. I bought a new coat in the sales, but apart from that, I haven’t desired any new clothes. I’m sorry for the fashion industry I suppose, but I’ve learned to be very happy with the wardrobe full that I already have, re-discovered some things I haven’t worn in a very long time and learned to love comfortable.

So, though I will not mourn the end of the pandemic (we have lost too much for that) I hope that we will all reflect a little and think about what we learned was important.

How do you feel about the end of restrictions?

Marian Keyes – Grown Ups to be precise. It was my book club’s choice the last time we met in person and although it was probably not a book I would have picked up it was the most perfect tonic, especially as I listened to it on audio, with Marian’s wonderful narration.

Marian Keyes – Grown Ups to be precise. It was my book club’s choice the last time we met in person and although it was probably not a book I would have picked up it was the most perfect tonic, especially as I listened to it on audio, with Marian’s wonderful narration.

The book concerns two women, Rosemary, an 86 year-old widow, and Kate, a 26 year-old journalist, and how they are brought together by chance when the Brixton lido is threatened with closure. Their relationship evolves as together they mount a campaign to keep the pool open, drawing in other local people and reviving a community spirit that everyone involved thought had been lost. In some ways the two women could not be more different: Rosemary is nearing the end of her life, now alone having lost her beloved husband, and has lived in this area of South London all her life. Kate, on the other hand, is young and bright, and has moved to the city from Bristol to begin her journalistic career on the local paper. Kate too, though, is lonely; unlike Rosemary she has not lost anyone, but she has not found anyone either, and she grapples with panic attacks, anxiety and low self-esteem. She shares a house with a number of similarly isolated flatmates, none of whom she knows, and stays alive thanks to ready meals.

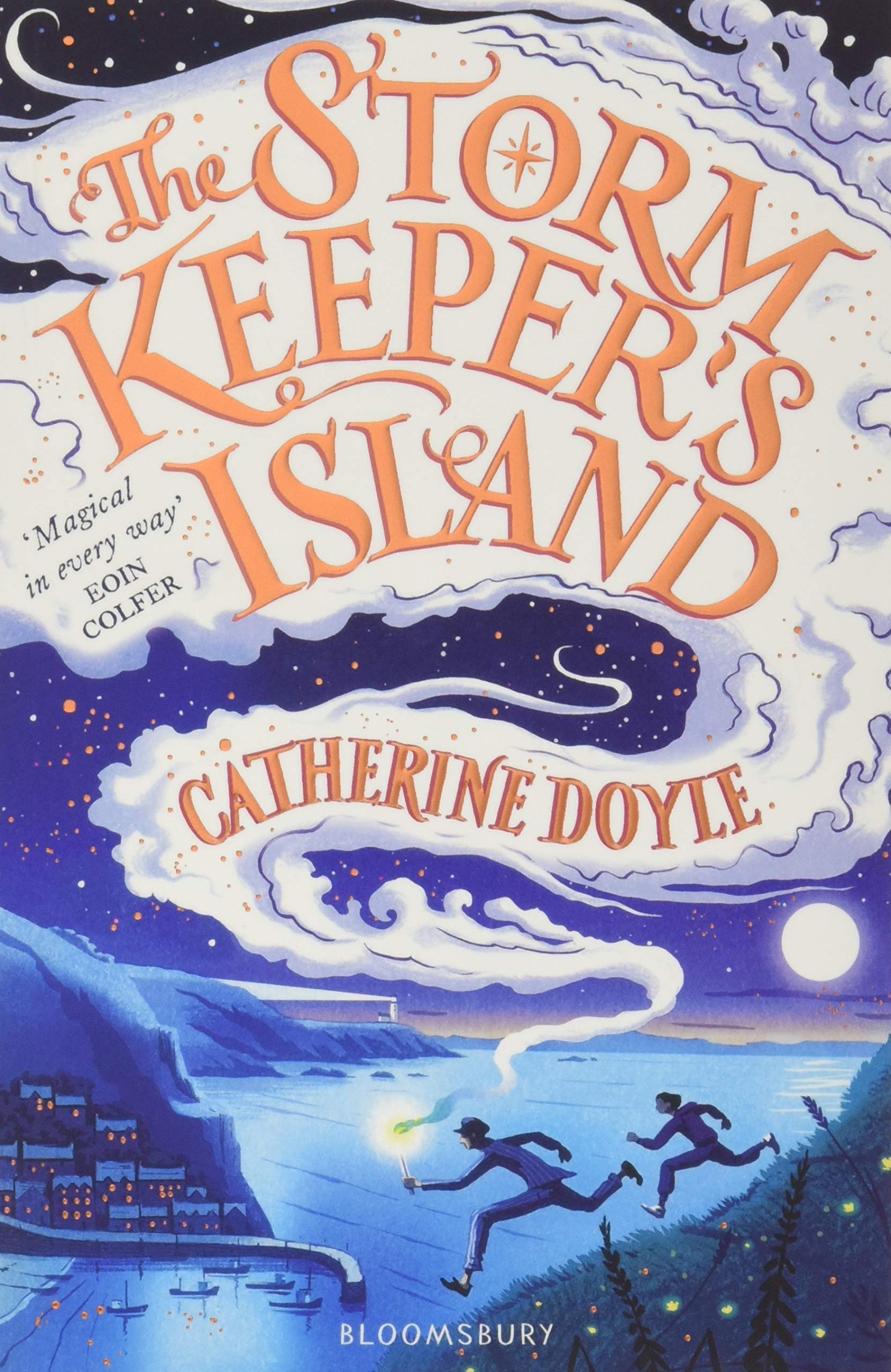

The book concerns two women, Rosemary, an 86 year-old widow, and Kate, a 26 year-old journalist, and how they are brought together by chance when the Brixton lido is threatened with closure. Their relationship evolves as together they mount a campaign to keep the pool open, drawing in other local people and reviving a community spirit that everyone involved thought had been lost. In some ways the two women could not be more different: Rosemary is nearing the end of her life, now alone having lost her beloved husband, and has lived in this area of South London all her life. Kate, on the other hand, is young and bright, and has moved to the city from Bristol to begin her journalistic career on the local paper. Kate too, though, is lonely; unlike Rosemary she has not lost anyone, but she has not found anyone either, and she grapples with panic attacks, anxiety and low self-esteem. She shares a house with a number of similarly isolated flatmates, none of whom she knows, and stays alive thanks to ready meals. This month, I would like to recommend Catherine Doyle’s The Storm Keeper’s Island, published last year by Bloomsbury, as a fantastic choice for any young people you know who like modern adventure stories where the good guy wins. Catherine Doyle is a young writer (just 29 years old) and has published several YA novels already; The Storm Keeper’s Island is her first novel for what is called the “middle grade”, ie about 9-12 years, and it was a barn-storming debut, winning several prizes and accolades from established authors in this genre. A second novel, following the further adventures of the main character Fionn Boyle, is planned for this summer and I would expect it to feature heavily in recommended holiday reading lists in advance of the Summer Reading Challenge.

This month, I would like to recommend Catherine Doyle’s The Storm Keeper’s Island, published last year by Bloomsbury, as a fantastic choice for any young people you know who like modern adventure stories where the good guy wins. Catherine Doyle is a young writer (just 29 years old) and has published several YA novels already; The Storm Keeper’s Island is her first novel for what is called the “middle grade”, ie about 9-12 years, and it was a barn-storming debut, winning several prizes and accolades from established authors in this genre. A second novel, following the further adventures of the main character Fionn Boyle, is planned for this summer and I would expect it to feature heavily in recommended holiday reading lists in advance of the Summer Reading Challenge. The central character is Walker, a man from rural Nova Scotia, who fought with the Allied forces in the D-Day landings. He has seen and experienced terrible events, death and injury that most of us can barely even imagine, and he survived. After the end of the war, he goes back to the United States and finds himself living among the homeless in New York City. The book is divided into four sections: 1946, 1948, 1951 and 1953 each set in a different US city (though Los Angeles is the setting for both 1948 and 1953). As he reflects on his experiences, it becomes clear that it was impossible for him to return home to Canada. He reminisces about the quiet, gentle life he led there, where the rhythms of the seasons, the dependence on the harvests of the seas, and community events (such as village hall dances) dominate everyone’s existence. It’s as if the contrast between that life and the brutality he witnessed in the war means he fears contaminating the innocence of those he has left behind. He can never go back, never unsee what he has seen, and those he once loved will never be able to understand how he has been changed.

The central character is Walker, a man from rural Nova Scotia, who fought with the Allied forces in the D-Day landings. He has seen and experienced terrible events, death and injury that most of us can barely even imagine, and he survived. After the end of the war, he goes back to the United States and finds himself living among the homeless in New York City. The book is divided into four sections: 1946, 1948, 1951 and 1953 each set in a different US city (though Los Angeles is the setting for both 1948 and 1953). As he reflects on his experiences, it becomes clear that it was impossible for him to return home to Canada. He reminisces about the quiet, gentle life he led there, where the rhythms of the seasons, the dependence on the harvests of the seas, and community events (such as village hall dances) dominate everyone’s existence. It’s as if the contrast between that life and the brutality he witnessed in the war means he fears contaminating the innocence of those he has left behind. He can never go back, never unsee what he has seen, and those he once loved will never be able to understand how he has been changed.

Eleanor communicates poorly with others, being rather too literal and pedantic for most people to tolerate and is therefore unable to form effective relationships. At first, she is not an easy character to love, except that we as readers know a couple of things about her that her workmates do not, and which make us more sympathetic to her. Firstly, we know she drinks herself into oblivion at the weekends: as a reader we are bound to ask what she is trying to escape from. Second, there is Eleanor’s mother, with whom she speaks every Wednesday evening; “Mummy” is controlling, manipulative, cruel, nasty. Eleanor is an adult and yet there is something disturbing about the way she always refers to her parent as a child would (never ‘Mum’ or ‘my mother’). The fact that Eleanor also receives regular monitoring visits from social workers tells us that there is something dark in Eleanor’s past that has contributed to her present quirkiness, but we are not told what.

Eleanor communicates poorly with others, being rather too literal and pedantic for most people to tolerate and is therefore unable to form effective relationships. At first, she is not an easy character to love, except that we as readers know a couple of things about her that her workmates do not, and which make us more sympathetic to her. Firstly, we know she drinks herself into oblivion at the weekends: as a reader we are bound to ask what she is trying to escape from. Second, there is Eleanor’s mother, with whom she speaks every Wednesday evening; “Mummy” is controlling, manipulative, cruel, nasty. Eleanor is an adult and yet there is something disturbing about the way she always refers to her parent as a child would (never ‘Mum’ or ‘my mother’). The fact that Eleanor also receives regular monitoring visits from social workers tells us that there is something dark in Eleanor’s past that has contributed to her present quirkiness, but we are not told what. This is Gail Honeyman’s first novel and it is a stunning achievement. A thoroughly enjoyable read. In an era where poor mental health, social isolation and dysfunctional relationships seem to have reached epidemic proportions, this novel is both an examination of one person’s particular circumstances and an antidote. Highly recommended.

This is Gail Honeyman’s first novel and it is a stunning achievement. A thoroughly enjoyable read. In an era where poor mental health, social isolation and dysfunctional relationships seem to have reached epidemic proportions, this novel is both an examination of one person’s particular circumstances and an antidote. Highly recommended.