I don’t read many thrillers. They’re not usually my ‘thing’. Sometimes I think it’s simply because the covers put me off! They seem invariably to have neon writing with a black background (as in fact, does this book) and sensational taglines designed to suck you in. The tagline here reads “I’m in a coma. My husband doesn’t love me anymore.” I’m afraid that, in my experience, books that promise much on the front cover deliver somewhat less between the pages. And, yes, that could indeed be true of life in general!

So, I approached this book with some apprehension. I probably would not have chosen it myself, but it was suggested by my book club. That said, I was open-minded, having been equally sceptical about Disclaimer by Renee Knight (also neon writing on a black background), which was suggested by a book club I used to belong to, and which I thoroughly enjoyed. (You can read my review of that book here.)

The central character is Amber, a married woman in her mid-30s, who when we first meet her, on Boxing Day 2016, is lying in hospital in a coma. She is also our narrator. The chapters alternate between ‘Now’, ie Amber lying in her hospital bed, ‘Then’, looking back over the days of the previous week and the events which have brought Amber to this position, and ‘Before’, looking back at Amber’s childhood. It is clear that Amber has been involved in some sort of car accident, although the circumstances are mysterious. As the narrative progresses we are drip-fed information about the other characters in the story and the part they have each played in bringing about Amber’s near-death.

Amber works in radio on a popular morning show called Coffee Morning with the very unpleasant but very powerful Madeline Frost, who is nothing short of a bully towards everyone else involved in the show, but who is loved by her audience. Amber is married to Paul, a struggling author, whose movements in the pre-Christmas week are suspicious. She also has a sister, the rather too-perfect Claire, who is attractive, confident, and a mother of twins, where Amber is under-achieving, stuck in a career rut and apparently infertile. There is also the sense that the relationship between Amber and Claire is not all that it seems at first; increasingly we see Claire as controlling and rather too controlled. It is clear that this dynamic has had some sort of impact on Amber’s present situation. A further character enters the book part-way through, Edward, a former boyfriend of Amber’s who she bumps into in London one evening. There is the suggestion that perhaps Amber chose the wrong guy when she married Paul.

Thus the scene is set, with our vulnerable central character and a full complement of secondary figures, each of whom could have dunnit. It’s a complex plot, which at times I found difficult to follow; perhaps this is my problem with thrillers – complexity seems to be prized above all else. There is cleverness in the way some parts of it are handled, however, I also felt there was rather too much going on. For example, not wishing to give anything away, I felt the Edward sub-plot was superfluous, and Amber’s OCD was unnecessary and rather randomly included.

I did enjoy the book, it’s certainly a page-turner, but the ending left me vaguely dissatisfied. Perhaps it is fashionable to have ambiguous conclusions, or perhaps the author is planning a sequel, but in a thriller, a genre where questions are continuously posed, I want answers, I want loose ends tied up, and I don’t want to be left hanging.

It’s a decent beach read if you’re off on your holidays soon.

It’s basically a book about sickness, and the various forms it takes; the sickness of the troubled central character, Yeong-hye, whose decision to renounce meat from her diet is the catalyst to a catastrophic sequence of events; the sickness of some of her relatives who simply cannot accept Yeong-hye’s decision or who use it to perpetrate their own base acts; and the sickness in the society which degrades and dehumanises Yeong-hye. The insidious and malevolent control meted out to Yeong-hye over a period of many years (a control that was legitimised by social and cultural norms) leads to her attempting to starve herself in a desperate attempt to assert her autonomy, and this has explosive consequences

It’s basically a book about sickness, and the various forms it takes; the sickness of the troubled central character, Yeong-hye, whose decision to renounce meat from her diet is the catalyst to a catastrophic sequence of events; the sickness of some of her relatives who simply cannot accept Yeong-hye’s decision or who use it to perpetrate their own base acts; and the sickness in the society which degrades and dehumanises Yeong-hye. The insidious and malevolent control meted out to Yeong-hye over a period of many years (a control that was legitimised by social and cultural norms) leads to her attempting to starve herself in a desperate attempt to assert her autonomy, and this has explosive consequences

This was April’s choice for my book club and one of the members described it as the best book we have read – she consumed it in virtually one sitting in the middle of the night when she was wide awake with jet lag! A fine endorsement indeed. It really is a marvellous book and, as I so often say on this blog, totally unfair that one so young should exhibit this much talent in a debut novel! It has also been shortlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction this year (winner to be annonced on 7 June), so it’s hot.

This was April’s choice for my book club and one of the members described it as the best book we have read – she consumed it in virtually one sitting in the middle of the night when she was wide awake with jet lag! A fine endorsement indeed. It really is a marvellous book and, as I so often say on this blog, totally unfair that one so young should exhibit this much talent in a debut novel! It has also been shortlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction this year (winner to be annonced on 7 June), so it’s hot.

What is so immediately intriguing about the title of the novel, of course, is that Holland is very, very flat. But In the Dutch Mountains imagines a world where the Netherlands extends much further south of its modern borders to northern Spain and the Pyrenees (hence the Dutch mountains). The narrator is himself a Spaniard, a civil servant who not only relates the story, but also philosophises on the processes of writing and story-telling: a story within a story. The main characters in the tale are Kai and Lucia, a slightly other-worldly circus couple, remarkable for their physical perfection, who are relieved of their jobs (because times have moved on and audience tastes have changed) and find themsleves travelling south to look for work. Kai is kidnapped and Lucia sets out on a journey to find him, accompanied by an old woman she meets on the way who agrees to drive her to find her lover.

What is so immediately intriguing about the title of the novel, of course, is that Holland is very, very flat. But In the Dutch Mountains imagines a world where the Netherlands extends much further south of its modern borders to northern Spain and the Pyrenees (hence the Dutch mountains). The narrator is himself a Spaniard, a civil servant who not only relates the story, but also philosophises on the processes of writing and story-telling: a story within a story. The main characters in the tale are Kai and Lucia, a slightly other-worldly circus couple, remarkable for their physical perfection, who are relieved of their jobs (because times have moved on and audience tastes have changed) and find themsleves travelling south to look for work. Kai is kidnapped and Lucia sets out on a journey to find him, accompanied by an old woman she meets on the way who agrees to drive her to find her lover. I’m off on a short holiday to the Netherlands so I’m planning to take some reading with me, of course, and have decided on another book from my

I’m off on a short holiday to the Netherlands so I’m planning to take some reading with me, of course, and have decided on another book from my  Nina is twenty when we meet her in the early 1980s. She lives with Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the London Review of Books, and her two young sons, Sam and Will, to whom she is a nanny. They live at 55 Gloucester Crescent NW1, an area that was also home to other literary types, among them Alan Bennett and Claire Tomalin, who also make appearances in the book, particularly ‘AB’ who is a great friend of ‘MK’.

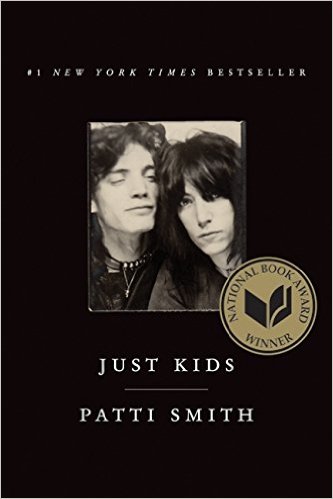

Nina is twenty when we meet her in the early 1980s. She lives with Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the London Review of Books, and her two young sons, Sam and Will, to whom she is a nanny. They live at 55 Gloucester Crescent NW1, an area that was also home to other literary types, among them Alan Bennett and Claire Tomalin, who also make appearances in the book, particularly ‘AB’ who is a great friend of ‘MK’. I’ve been an admirer of Patti Smith for a number of years now. I’m a bit young to have been a fan of hers when she first broke onto the music scene in the mid-1970s. I became aware of her much later when I picked up a sale copy of her debut album Horses. I was also aware of Robert Mapplethorpe, the late artist-photographer who was her lover and then close friend when they were both very young. Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989 and it must have been in the 1990s that I saw an exhibition of his work in London (I had an interest in photography at the time). Later on again I learned about the connection between the two and how Patti had been, if you like, Mapplethorpe’s ‘muse’ when he was first discovering his art.

I’ve been an admirer of Patti Smith for a number of years now. I’m a bit young to have been a fan of hers when she first broke onto the music scene in the mid-1970s. I became aware of her much later when I picked up a sale copy of her debut album Horses. I was also aware of Robert Mapplethorpe, the late artist-photographer who was her lover and then close friend when they were both very young. Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989 and it must have been in the 1990s that I saw an exhibition of his work in London (I had an interest in photography at the time). Later on again I learned about the connection between the two and how Patti had been, if you like, Mapplethorpe’s ‘muse’ when he was first discovering his art.