I have probably spent more time listening to audiobooks in the last twelve months than in all of the previous four years of subscribing to an audiobook service put together! There were in fact times in those previous four years when I suspended my membership because I was building up so many credits. I mainly listened to them on long drives alone and these were relatively infrequent. Last year, however, I found myself, like many people, going out for a walk or run daily. I haven’t walked more in the last twelve months than I did before, but my walking these days is less about purpose (going somewhere to get something) and more about pleasure, nature and exercise, and, well, let’s be honest, because when something is rationed you realise how important it is to you.

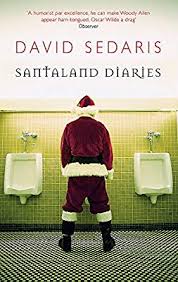

I’ve reviewed a number of my particular favourite audiobooks on here: Andrew Taylor’s Ashes of London series (I listened to three out of the four last year), Douglas Stuart’s Booker Prize-winning Shuggie Bain, and of course David Sedaris’s Santaland Diaries. I have yet to review the audiobook that was the absolute standout for me in 2020, though, and which I listened to in the autumn – The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. I can only put my reticence in posting a review down to being in complete awe of Tartt’s genius as a writer, and the feeling that I could never write anything that would in any way do justice to the mastery on display in this book.

I will try and summarise the plot as briefly as possible. We first meet the main character Theodore “Theo” Decker when he is thirteen years old. He lives with his mother, who works on an art journal, in New York City, his alcoholic father having left the family some years earlier. Theo is in some difficulty at school and he and his mother have an appointment with the Principal. To kill time before the meeting, Theo’s mother takes him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A terrorist bomb explodes while they are there, killing Theo’s mother and many others, and devastating the building. In the middle of the wreckage Theo spots an elderly man, whom he had noticed earlier on in the visit because he was accompanied by a sullen, but ephemeral looking young girl of about Theo’s age, carrying an instrument case. Theo goes to the old man, who is dying from his injuries. The old man gives Theo a ring from his finger and a curious message which it will later transpire refers to an antique shop that he Welty Blackwell, ran with his partner James “Hobie” Hobart. During their brief time together, in what was a room devoted to Dutch paintings from the 17th century, Theo finds himself captivated by a tiny picture by Carel Fabritius called The Goldfinch. Welty notices Theo’s fascination and with his dying breath seems to encourage Theo to take it. The explosion scene is compulsive listening, jaw-dropping.

Theo takes the painting and manages to find his own way out. He takes cover back at home, not knowing if his mother is alive or dead. Eventually, the authorities track him down and he is placed in temporary care with the family of a school friend, Andy Barbour, a slightly sickly, precociously intelligent boy, who, like Theo, does not quite fit in at school. Andy’s family is from the Upper East Side – wealthy, formal, slightly odd, and more than a little dysfunctional. But after a period of adjustment Theo and the family gradually get used to one another, until, at the point the Barbours announce that they would like formally to adopt Theo, the boy’s life takes a dramatic turn.

I wish to say nothing more of the plot, because it is simply too delicious and too clever and if you have not read the book yourself and are tempted to do so, I want you to enjoy every single moment of shock and drama.

Theo does not reveal that he has the painting for many years. And it burns in his conscience, influences almost all his actions and decisions. The plot is a joy, an absolute roller-coaster, and the character of Theo is complex and brilliantly-drawn. He is in turns damaged and damaging through the book, but all the while the two things that constantly influence his life are the catastrophic loss of his beloved mother in such traumatic circumstances, and the concealment of the painting, an extremely valuable internationally renowned piece, which becomes the subject of a worldwide search. Theo’s increasing paranoia in relation to the painting, has echoes of The Picture of Dorian Gray. In addition to Theo there are a clutch of other superb characters: Boris, his Nevada schoolfriend who becomes a major influence on events in his life; Hobie, the business partner of the old dying man in the museum who Theo tracks down; Pippa, the young girl with the music case, Welty’s granddaughter; and, of course, Theo’s mother, who, although she dies early, is a constant presence in the narrative.

This book has everything: brilliant characters, brilliant plot, action, reflection, literary merit. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Donna Tartt in 2014 (my second Pulitzer Prize-winner reviewed in a week!) and was adapted for screen in 2019. I’m not sure I want to see the film. There is surely no way it could do justice to the book? Although I note that it has Nicole Kidman and Sarah Paulson among the cast so I’m tempted.

I have no idea why I have not read this before; The Secret History, Donna Tartt’s debut novel, published in 1992, is one of my favourite books of all time, a masterpiece, so you would have thought I’d be hanging on everything she has ever written. She is hardly prolific though – her second book, The Little Friend, did not come until ten years after her first, in 2002. That was the start of my childbearing, aka reading wilderness, years, so I’m not really surprised I didn’t get around to that one. Tartt’s books are long – The Goldfinch is 880 pages, or 32 hours of listening joy, and The Little Friend is almost 600 pages – there was no way I would have got through that with a two year old!

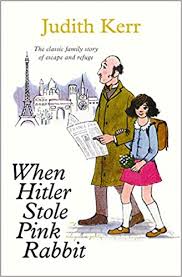

The Goldfinch is highly, highly recommended. And the painting, a fragment of which is shown on the cover of the book, is utterly beautiful. That’s it, I’m out of superlatives.