As has become customary, I was somewhat late posting on my Reading Challenge Facebook Group with this month’s title, the theme of which is a novel from Eastern Europe. I have chosen Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. This book has been sitting on my bookshelves for many years; it was part of my husband’s collection before we met, so must have been bought at least 25 years ago. I’ve ‘been meaning to read it’ ever since. There may well be books on my own TBR pile that have been around even longer, but I am determined I will get to them all one day! So, this month’s theme provides the perfect opportunity to get into this particular title, a renowned modern classic set against the background of the Prague Spring in 1968. First published in 1984, it was made into a film in 1988, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche. Apparently, the author hated the film!

So, if you would like to join me this month, I would love to hear your thoughts at the end of the month – or, at my present rate of reading, a week or so into October!

Last month’s theme was ‘a love story’ and I chose André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name. The novel is set primarily during one sultry Italian summer in the 1980s. The younger main character, teenager Elio, spends every summer there with his parents at their home. Each year they invite an American graduate student to stay with them for several weeks, to assist Elio’s father with his academic work, whilst also working on a project of their own. This has become a tedious routine for Elio, who is always aggrieved that, for the period of the visit, he has to vacate his bedroom for a smaller one down the hall, so that the guest can stay in more comfort. That is until Oliver arrives. Seven years older than Elio he is confident, outgoing, charming and brilliant, a favourite with Elio’s parents, the staff who work in the house, and the family’s local friends and neighbours. By contrast, Elio is introverted, at times morose, a typical teenager, you might say.

The book is written from Elio’s point of view, so we know he feels an instant attraction to Oliver. Still young, Elio is in the early stage of exploring his sexuality. Although he has no apparent qualms about homosexuality, he clearly does not feel he can explore this openly in front of his family. He feels sure the attraction is mutual, but is frustrated by Oliver’s reluctance to engage with him. Initially, there is an intense psychological dance between the two, as both young men try to suppress their feelings, even having romantic liaisons with other women. When Elio confronts Oliver about what he sees as his cruelty, Oliver expresses his concern about their age difference and whether it would be unfair to expose him to potential heartache. Oliver is concerned about the power imbalance that the age difference confers.

The pair finally come together and for the last few weeks of Oliver’s stay they have an intense sexual relationship and experience a deep emotional connection. Like all holiday romances, however, it cannot last. There is no sad ending, however, merely a recognition, that such love affairs burn hot and bright, but never for long.

A fellow reader commented that the time in which this novel is set is a factor. That if it had been, say, 10 or 15 years later, perhaps the romance would have been more acceptable (and perhaps less intense?). For me, the ‘forbidden’ nature of it came more from the age and status difference – Elio is at an early stage of sexual awakening, while Oliver is more experienced and does not want Elio’s early formative sexual experience to be one that he may regret later in life. Perhaps this does reflect the fact that homosexuality was still considered a more niche interest, less socially mainstream and more likely to cause psychological harm if later rejected.

This was a perfect novel for late August; I had planned to enjoy it on my summer holiday, lazing on the patio, but alas my holiday was cut short, so I had to make do with reading it in cool rainy south Manchester! It was good to escape to Italy in this book though.

I liked the story, the tension created felt very real and the ending was good. Apparently, the follow-up, Find Me is not as good. The characters were strong and the sense of place was very powerfully drawn, probably my favourite aspect of the book. It has of course been made into a film, starring Timothy Chalemet and Armie Hammer, which was highly praised and the breakthrough movie for its young star, Chalemet. I am also told the audiobook, read by Hammer, is excellent.

Recommended.

I had been thinking about some of the classic love stories – Jane Eyre, Anna Karenina, Gone with the Wind, The Remains of the Day – but none of these felt much like ‘holiday reading’. But then a bit of online research threw up the perfect suggestion – Call Me By Your Name by Andre Aciman. First published in 2007, this novel was made into a very successful film in 2018 starring Timothee Chalemet and Armie Hammer. It is set in the 1980s on the Italian Riviera (perfect!) and concerns a romance between Italian-American Elio (Chalemet), spending the long hot summer at his parents’ holiday home, and visiting academic Oliver (Hammer). It is apparently quite steamy (perfect!). I have not yet seen the film, so I am delighted to read the book first.

I had been thinking about some of the classic love stories – Jane Eyre, Anna Karenina, Gone with the Wind, The Remains of the Day – but none of these felt much like ‘holiday reading’. But then a bit of online research threw up the perfect suggestion – Call Me By Your Name by Andre Aciman. First published in 2007, this novel was made into a very successful film in 2018 starring Timothee Chalemet and Armie Hammer. It is set in the 1980s on the Italian Riviera (perfect!) and concerns a romance between Italian-American Elio (Chalemet), spending the long hot summer at his parents’ holiday home, and visiting academic Oliver (Hammer). It is apparently quite steamy (perfect!). I have not yet seen the film, so I am delighted to read the book first. At the start of this novel Nurit is divorced, ghost-writing money-spinner books for celebrities and somewhat directionless. Her affair with Rinaldi is long over, but he contacts her and asks her to write some columns on Chazarreta’s murder. He arranges for her to stay at the home of his newspaper’s proprietor at La Maravillosa so that she can get close to the scene of the crime and the people who live there. It was Rinaldi who called Nurit ‘Betty Boo’, because of her dark eyes and dark curly hair. As Nurit gradually becomes immersed in the crime, her relationship develops with two other journalists at El Tribuno, which her ex-lover edits: Jaime Brena, the disillusioned middle-aged hack, former crime journalist, now reduced to the lifestyle section of the paper, and ‘Crime Boy’ the young upstart, now the lead crime writer on the paper, who, with his limited experience, turns increasingly to Brena for help on the Chazarreta case.

At the start of this novel Nurit is divorced, ghost-writing money-spinner books for celebrities and somewhat directionless. Her affair with Rinaldi is long over, but he contacts her and asks her to write some columns on Chazarreta’s murder. He arranges for her to stay at the home of his newspaper’s proprietor at La Maravillosa so that she can get close to the scene of the crime and the people who live there. It was Rinaldi who called Nurit ‘Betty Boo’, because of her dark eyes and dark curly hair. As Nurit gradually becomes immersed in the crime, her relationship develops with two other journalists at El Tribuno, which her ex-lover edits: Jaime Brena, the disillusioned middle-aged hack, former crime journalist, now reduced to the lifestyle section of the paper, and ‘Crime Boy’ the young upstart, now the lead crime writer on the paper, who, with his limited experience, turns increasingly to Brena for help on the Chazarreta case.

The premise of the story is very simple: So-nyo is a wife and mother to five children, all of whom are now grown-up and living their lives in different parts of the country (South Korea). So-nyo lives a very simple fairly rural life with her husband at the family home, where there are many privations. The place is almost a throwback to a bygone era. So-nyo’s eldest son, Hyong-chol, lives in Seoul with his wife and family and it is while his parents are on their way to visit him (to celebrate the father’s birthday) that his mother goes missing; she was holding her husband’s hand on the busy underground station platform one moment, then she seemed to slip from his grasp and just disappeared into the crowd.

The premise of the story is very simple: So-nyo is a wife and mother to five children, all of whom are now grown-up and living their lives in different parts of the country (South Korea). So-nyo lives a very simple fairly rural life with her husband at the family home, where there are many privations. The place is almost a throwback to a bygone era. So-nyo’s eldest son, Hyong-chol, lives in Seoul with his wife and family and it is while his parents are on their way to visit him (to celebrate the father’s birthday) that his mother goes missing; she was holding her husband’s hand on the busy underground station platform one moment, then she seemed to slip from his grasp and just disappeared into the crowd. By the strangest of coincidences, I have also just read two books which also explore issues of race and class. Rebecca Skloot’s non-fiction work The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, and The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Skloot’s book is a detailed and complex account of one woman, Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman from Virginia who died in 1951 from aggressive cervical cancer. The cancer cells from her body were special and unique because they were the first ever cells that were able to not only survive outside their host, but were able to continue to thrive and reproduce, at a rapid rate. This perhaps accounts for the very aggressive nature of Henrietta’s disease. Scientists used these cells, known universally as HeLa cells, to create trillions and trillions more of them, which have been used ever since, worldwide and have been directly responsible for the development of life-saving drugs and treatments, for example for polio. The key to the story, however, is that Henrietta died without ever having been advised about or consenting to the use of her cells in this way, neither did her family, and none of her surviving relatives have been given any financial compensation. What makes the story all the more shocking, however, is that Henrietta died at a time of segregation, and almost certainly did not receive the same level of care and respect as a white woman would have done. I will write more about this book in a future post because it is a fascinating story.

By the strangest of coincidences, I have also just read two books which also explore issues of race and class. Rebecca Skloot’s non-fiction work The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, and The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Skloot’s book is a detailed and complex account of one woman, Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman from Virginia who died in 1951 from aggressive cervical cancer. The cancer cells from her body were special and unique because they were the first ever cells that were able to not only survive outside their host, but were able to continue to thrive and reproduce, at a rapid rate. This perhaps accounts for the very aggressive nature of Henrietta’s disease. Scientists used these cells, known universally as HeLa cells, to create trillions and trillions more of them, which have been used ever since, worldwide and have been directly responsible for the development of life-saving drugs and treatments, for example for polio. The key to the story, however, is that Henrietta died without ever having been advised about or consenting to the use of her cells in this way, neither did her family, and none of her surviving relatives have been given any financial compensation. What makes the story all the more shocking, however, is that Henrietta died at a time of segregation, and almost certainly did not receive the same level of care and respect as a white woman would have done. I will write more about this book in a future post because it is a fascinating story. The other book I have been reading, The Water Dancer, concerns the story of Hiram, a black slave also in Virginia in the mid-1800s. His mother was also a slave, but his father was a slave-owner, who allowed his son some elementary education after his mother’s death and then, when he was in his teens, gave him the special status of being the personal servant to his white half-brother, Maynard, the heir to their father’s estate. Hiram is also the grandchild of legendary slave Santi-Bess, one of the original transported Africans who is said to have had magical powers (Conduction), although it does not become entirely clear what these are until towards the end of the book. The first significant glimpse of this is when, whilst chaperoning Maynard on a drunken night out, the two young men somehow end up in the river. Maynard drowns but Hiram somehow emerges alive. The events which follow Maynard’s death eventually afford Hiram the opportunity to escape slavery via the Underground and he soon becomes an agent of that cause. It is not a straightforward choice for him, though, as he is forced to confront traumatic memories of his mother, who died when he was very young, and to face the many complex facets of slavery, its consequences, its victims and what it means to be free.

The other book I have been reading, The Water Dancer, concerns the story of Hiram, a black slave also in Virginia in the mid-1800s. His mother was also a slave, but his father was a slave-owner, who allowed his son some elementary education after his mother’s death and then, when he was in his teens, gave him the special status of being the personal servant to his white half-brother, Maynard, the heir to their father’s estate. Hiram is also the grandchild of legendary slave Santi-Bess, one of the original transported Africans who is said to have had magical powers (Conduction), although it does not become entirely clear what these are until towards the end of the book. The first significant glimpse of this is when, whilst chaperoning Maynard on a drunken night out, the two young men somehow end up in the river. Maynard drowns but Hiram somehow emerges alive. The events which follow Maynard’s death eventually afford Hiram the opportunity to escape slavery via the Underground and he soon becomes an agent of that cause. It is not a straightforward choice for him, though, as he is forced to confront traumatic memories of his mother, who died when he was very young, and to face the many complex facets of slavery, its consequences, its victims and what it means to be free. The Silence of the Girls has been critically-acclaimed and was shortlisted for last year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. I really, really wanted to love this book, but I’m afraid I didn’t. It could be that the timing was wrong – December for me was mad busy so I read the book in short bursts over a longish period when I was quite stressed. I don’t think I gave it the time and attention it deserved. But then, neither did it really grab me when perhaps it ought to have done.

The Silence of the Girls has been critically-acclaimed and was shortlisted for last year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction. I really, really wanted to love this book, but I’m afraid I didn’t. It could be that the timing was wrong – December for me was mad busy so I read the book in short bursts over a longish period when I was quite stressed. I don’t think I gave it the time and attention it deserved. But then, neither did it really grab me when perhaps it ought to have done. This book grabbed me by the throat right from the outset; I listened to it on audio (fantastic performances from the actors Julia Whelan and Kirby Haborne, by the way) and simply could not ‘put it down’. I got a lot of exercise in January, because going for a walk became an excuse to listen to a few more minutes’ worth!

This book grabbed me by the throat right from the outset; I listened to it on audio (fantastic performances from the actors Julia Whelan and Kirby Haborne, by the way) and simply could not ‘put it down’. I got a lot of exercise in January, because going for a walk became an excuse to listen to a few more minutes’ worth! A book I listened to at the end of last year was Ashes of London by Andrew Taylor. I borrowed it from the library when it was first published in 2017 but did not manage to get through it before I had to return it for someone else. It is a historical thriller set at the time of the Great Fire of London in September 1666 and is the first in Taylor’s Marwood & Lovett detective series. I have not yet read (or listened to) the second and third books in the series, both of which were published last year, but they sound intriguing.

A book I listened to at the end of last year was Ashes of London by Andrew Taylor. I borrowed it from the library when it was first published in 2017 but did not manage to get through it before I had to return it for someone else. It is a historical thriller set at the time of the Great Fire of London in September 1666 and is the first in Taylor’s Marwood & Lovett detective series. I have not yet read (or listened to) the second and third books in the series, both of which were published last year, but they sound intriguing. What I liked about it, however, was less this grander aspect, but rather the quality of its story-telling. I must admit that 50 or so pages in, I was not overwhelmed! There are twelve characters in the book, all women bar one (who is trans), all black or mixed race. They are broken down into four groups of three, and each threesome is strongly connected in some way (eg mother/daughter). Each group is also connected with the others, even if only in a tenuous way (eg teacher and former pupil) and almost all are in some way connected to Amma, the first character we meet. Amma has written a play which is having its debut performance at the National and this provides the framework of the novel. Many of the characters are present at the penultimate chapter of the book, the after-party, where the differences between them and their lives are laid bare. This is interesting because the author is not only trying to draw out the similarities between the characters and their life experiences, suggested by their common characteristic of being mixed race and female, but she is also, I think, railing against the notion of such women/people being homogeneous; they are all far more than just their race or gender.

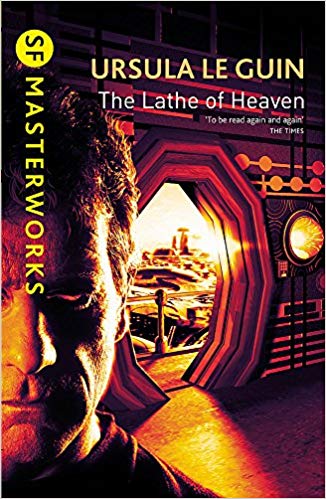

What I liked about it, however, was less this grander aspect, but rather the quality of its story-telling. I must admit that 50 or so pages in, I was not overwhelmed! There are twelve characters in the book, all women bar one (who is trans), all black or mixed race. They are broken down into four groups of three, and each threesome is strongly connected in some way (eg mother/daughter). Each group is also connected with the others, even if only in a tenuous way (eg teacher and former pupil) and almost all are in some way connected to Amma, the first character we meet. Amma has written a play which is having its debut performance at the National and this provides the framework of the novel. Many of the characters are present at the penultimate chapter of the book, the after-party, where the differences between them and their lives are laid bare. This is interesting because the author is not only trying to draw out the similarities between the characters and their life experiences, suggested by their common characteristic of being mixed race and female, but she is also, I think, railing against the notion of such women/people being homogeneous; they are all far more than just their race or gender. The Lathe of Heaven was written in 1971, but was set in ‘the future’ – Portland Oregon in 2002. This future world is one in which the global population is out of control, climate change has wrought irreparable damage and war in the Middle East threatens geopolitical stability. The most alarming (and engaging) thing about the book, for me, was how prophetic it was; in 1971 did readers think this was some dystopian world? Worryingly, many of the problems envisaged by Le Guin are recognisable features of our environment in 2019.

The Lathe of Heaven was written in 1971, but was set in ‘the future’ – Portland Oregon in 2002. This future world is one in which the global population is out of control, climate change has wrought irreparable damage and war in the Middle East threatens geopolitical stability. The most alarming (and engaging) thing about the book, for me, was how prophetic it was; in 1971 did readers think this was some dystopian world? Worryingly, many of the problems envisaged by Le Guin are recognisable features of our environment in 2019.