Hello, happy new year, happy Epiphany! I am late to the new year party this year. 2020 caused many of us to look at our lives somewhat afresh and ask what on earth we are doing and what is really important. One of the smallish things that I identified was an attachment to making Christmas something a bit more meaningful, in the absence of a religious faith, and I found myself taking an interest in some of the ancient secular traditions of the season. I tried not to do anything that looked too much like work between the winter solstice on the 20th/21st December (I watched the live sunset over Stonehenge broadcast on the English Heritage Facebook page and it was amazing) and twelfth night on 5th January (yes, I know many say it’s the 6th- depends when you start counting).

It was an odd period this time around for so many people. I was lucky; I collected my son from university in mid-December and with my husband and two daughters the five of us hunkered down, watched films, cooked, ate, walked, relaxed and generally had one of the nicest Christmasses ever. I’m not trying to be smug, especially if, denied the company and contact of loved ones, yours was s**t (and I know plenty of people for whom it was), I suppose all I’m saying is that we felt freer than usual of many of the normal Christmas pressures. And it was really very nice.

Our tree will come down today after a sterling four weeks of service. I switched off my Christmas lights for the last time yesterday night and I will miss them. I switched them on every morning when I came down to breakfast, still in the dark, and they were enormously cheering. I’ll need to find an alternative I think until the mornings are light again. I also lit candles in my front window every evening at dusk. That was nice too and I’m going to keep doing that until the evenings get a bit lighter.

So, today it’s back to work. My son scooted back to university at the weekend, relieved I think to have made the break for the border before Lockdown 3.o and the new travel restrictions came into force. My teenage daughters have diligently embraced the opportunities of online home learning – no more battling on public transport every day, no going out in the cold and dark, no school uniform and no classroom distractions from the handful of kids whose learning loss over the past few months has been so grave that they have forgotten how to behave in a classroom or towards their teachers. Sad, distressing and deeply worrying. Teachers, you have my utmost utmost respect for what you have done, achieved and had to put up with in 2020. I am lucky to have motivated children, old enough not to need supervision, able enough not to need much support and a household with enough tech and enough broadband to support a family of four online for most of the day. I am very very aware of my good fortune. It is a scandal that so many do not enjoy the last two things in order to cope with the first three.

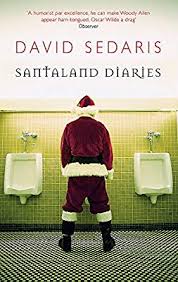

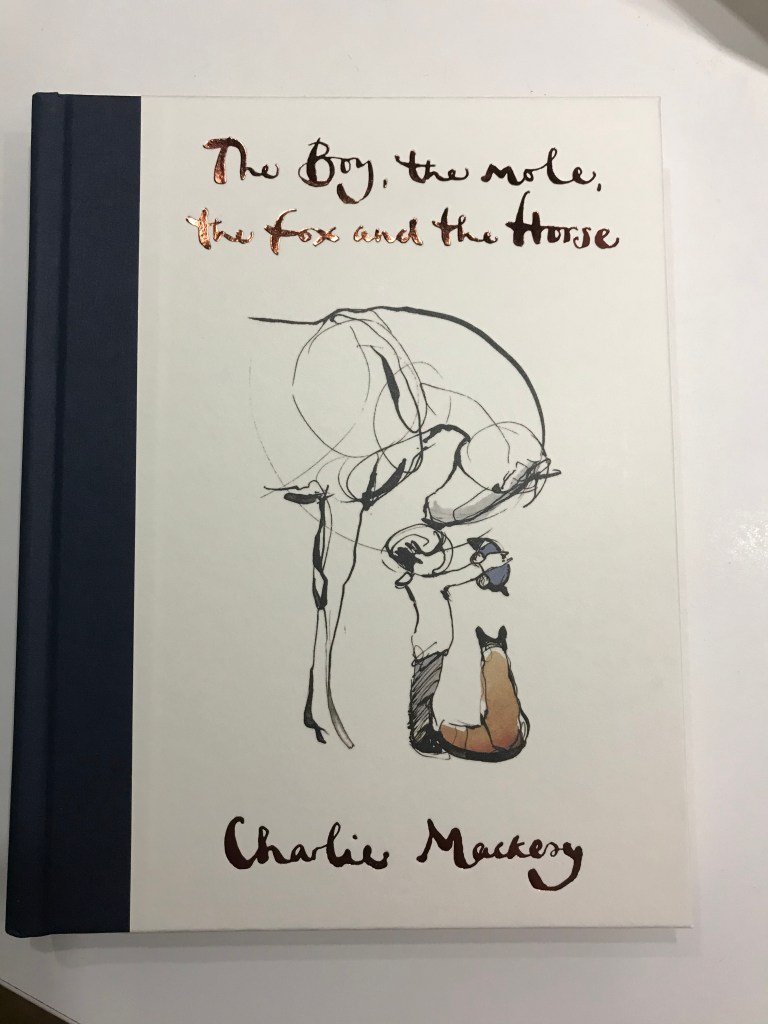

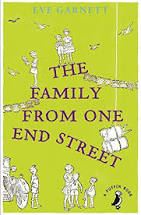

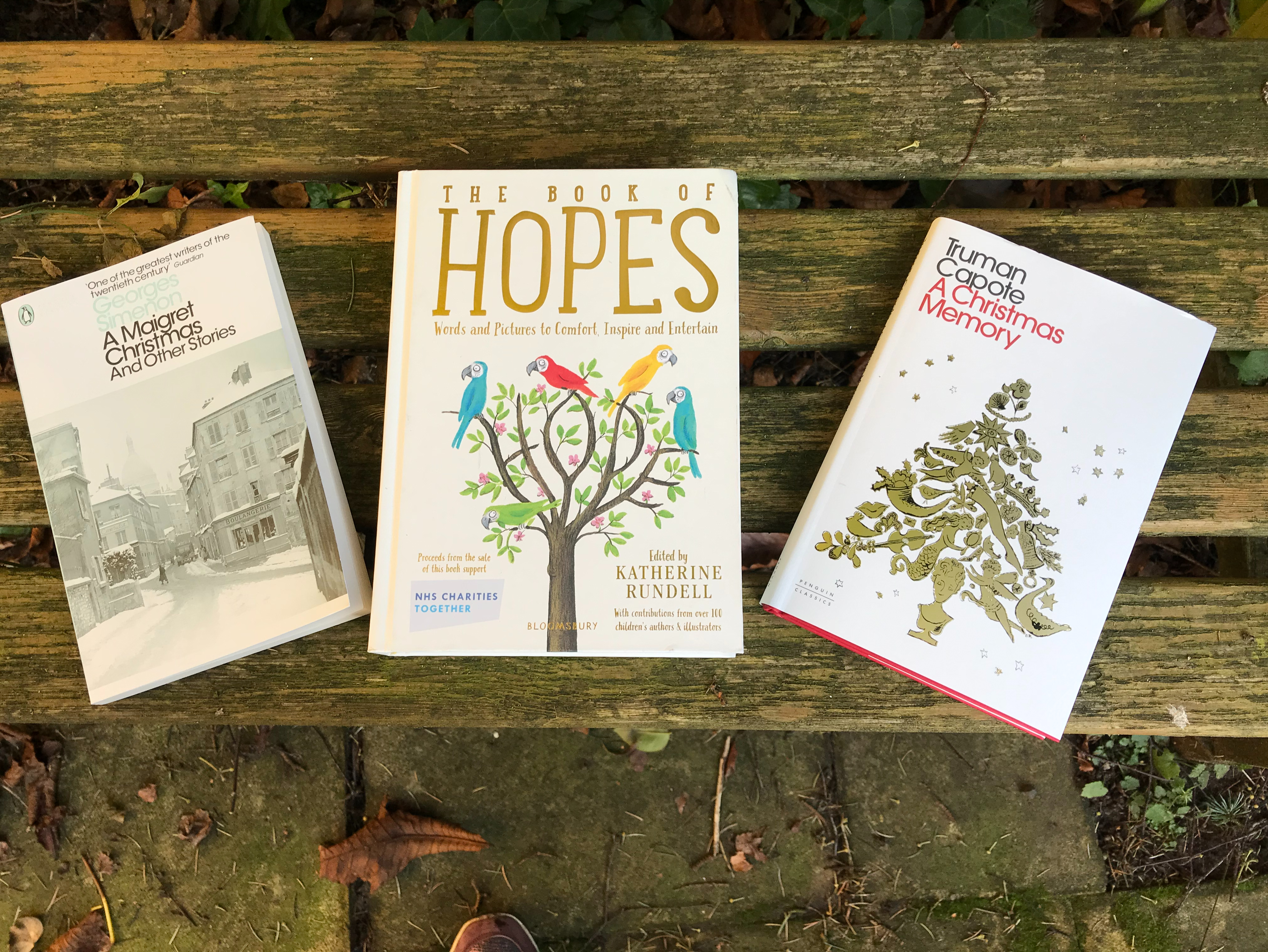

I spent a lot of time reading over the Christmas break (goodness is it really four weeks since I last posted?!), but not my usual fare. I read a load of short stories; I bought most of my Christmas gifts in my local bookshops, one of which is a chain with a loyalty scheme. I built up quite a nice bunch of points so on Christmas Eve I treated myself to the following books:

I’ve been working my way through these and it was a joy to dip in and out. More on these soon.

Now it is time to look forward, and 2021 promises much. The vaccine, oh the vaccine. Surely the scientific miracle of our age. Let us hope governments deliver. The inauguration of a new President in the United States, whom we hope will, alongside his stellar Vice-President-elect, lead the world, as only his country can do, in paying long overdue serious attention to climate change, and addressing social injustice in all its forms. Only fourteen more days to go. I think the rest of the world is counting.

Plus of course, there are the dozens of wonderful books we are due, and lots of cultural events coming up. And, on a more parochial note, there is of course my 2021 Facebook Reading Challenge! It’s been tough this time, coming up with themes (I’ve done the genres and I’ve done countries and continents), so I’m just doing a hybrid of previous years and re-using most of the themes in a different order or with a twist! Why not? It has thrown up some really wonderful reading choices that I would not otherwise have made so what is not to like?

My first book of the year, on the theme of an American classic, is a re-read for me, and not too long, since we are already nearly a week into the month – The Color Purple by Alice Walker. I would love for you to join me on my Facebook Reading Challenge this year. You can print out and keep my reading challenge pro forma below (:D) if you’d like to get involved, and join my Facebook group.

Happy reading everyone!