My usual routines, including my reading habits, are all over the place right now! What about you? I have both my daughters at home from school and my son home from university, plus my husband working from home. Although we are fortunate to have enough space and enough technology to enable everyone to do what they need to do, there are times when we get in each other’s way. I am also a creature of habit and do not always find it easy to adjust my rhythms to fit with other people’s. So, other commitments permitting, I like sit down with a cup of tea to read at around 3pm most afternoons, just before the return home from school. But, now, that is actually the busiest time of the day in our household – everyone seems to be ‘clocking off’ and wanting interaction! First world problems, as they say. We are all well, work is plentiful; we are among the more fortunate.

At times like this, I find it’s the little things that are important, so I try to find some time every day, no matter how small, to do some reading. I have several books on the go at the moment – Ulysses (which I promised myself I’d re-read this year and which I spent a glorious couple of hours simultaneously reading and listening to on Tuesday, 16th June, Bloomsday), Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light, The Beekeeper of Aleppo, which I’m listening to on audiobook, for my book club, and which is amazing, and my Facebook Reading Challenge choice for this month – The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives.

This book by Nigerian writer Lola Shoneyin, was published in 2010 and longlisted for the then Orange Prize for fiction the following year. Shoneyin writes beautifully. I have only just started it but I already love the characterisation and the humour, although a more melancholic note is now beginning to enter. It is described in the publisher’s blurb as at once funny and moving and I can definitely see that. Baba Segi is a traditional Nigerian male, still following the practice of polygamy in modern-day Nigeria. He has seven children by his first three wives, but desires more and when he meets Bolanle, a young graduate from a more enlightened family, who are against the marriage, he thinks his wish has been granted. Not all goes to plan, however.

This book by Nigerian writer Lola Shoneyin, was published in 2010 and longlisted for the then Orange Prize for fiction the following year. Shoneyin writes beautifully. I have only just started it but I already love the characterisation and the humour, although a more melancholic note is now beginning to enter. It is described in the publisher’s blurb as at once funny and moving and I can definitely see that. Baba Segi is a traditional Nigerian male, still following the practice of polygamy in modern-day Nigeria. He has seven children by his first three wives, but desires more and when he meets Bolanle, a young graduate from a more enlightened family, who are against the marriage, he thinks his wish has been granted. Not all goes to plan, however.

I am enjoying the exploration of the family dynamics – a polygamous household will be outside the experience of most Western readers – and how the relationships between the four wives are beginning to evolve.

If you would like to join me in my reading challenge this month, hop on over to the Facebook Group– there is still time! It’s a fairly short book and we are only just over halfway through the month; I might even finish on time this month!

How have your reading habits changed in these last few months?

If you have enjoyed this post, I would love for you to follow my blog. Let’s also connect on social media.

I really enjoyed Zennor in Darkness. It is a great story, two stories really, which become intertwined. Clare Coyne is the only daughter of widowed Francis Coyne, and the pair live together in the small town of Zennor in Cornwall. Clare’s mother was born there and the family moved from London when Clare was a baby in order to be near family. Clare’s father’s family had a higher social status, and Clare is clearly ‘different’ from her Cornish cousins, grandparents and aunts, with whom she has spent so much time, but Clare is largely disconnected from her paternal grandparents. Francis Coyne is an ineffectual character, a botanist who earns very little money from his publishing, who spends more time with his books than with his daughter, and who does not seem to understand her on any level. Clare has artistic ability and is a talented artist. She spends her time looking after her father, keeping house, and drawing plants for his latest book project.

I really enjoyed Zennor in Darkness. It is a great story, two stories really, which become intertwined. Clare Coyne is the only daughter of widowed Francis Coyne, and the pair live together in the small town of Zennor in Cornwall. Clare’s mother was born there and the family moved from London when Clare was a baby in order to be near family. Clare’s father’s family had a higher social status, and Clare is clearly ‘different’ from her Cornish cousins, grandparents and aunts, with whom she has spent so much time, but Clare is largely disconnected from her paternal grandparents. Francis Coyne is an ineffectual character, a botanist who earns very little money from his publishing, who spends more time with his books than with his daughter, and who does not seem to understand her on any level. Clare has artistic ability and is a talented artist. She spends her time looking after her father, keeping house, and drawing plants for his latest book project. The premise of the story is very simple: So-nyo is a wife and mother to five children, all of whom are now grown-up and living their lives in different parts of the country (South Korea). So-nyo lives a very simple fairly rural life with her husband at the family home, where there are many privations. The place is almost a throwback to a bygone era. So-nyo’s eldest son, Hyong-chol, lives in Seoul with his wife and family and it is while his parents are on their way to visit him (to celebrate the father’s birthday) that his mother goes missing; she was holding her husband’s hand on the busy underground station platform one moment, then she seemed to slip from his grasp and just disappeared into the crowd.

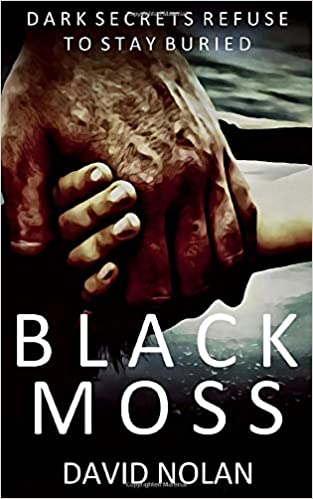

The premise of the story is very simple: So-nyo is a wife and mother to five children, all of whom are now grown-up and living their lives in different parts of the country (South Korea). So-nyo lives a very simple fairly rural life with her husband at the family home, where there are many privations. The place is almost a throwback to a bygone era. So-nyo’s eldest son, Hyong-chol, lives in Seoul with his wife and family and it is while his parents are on their way to visit him (to celebrate the father’s birthday) that his mother goes missing; she was holding her husband’s hand on the busy underground station platform one moment, then she seemed to slip from his grasp and just disappeared into the crowd. The book jumps back and forth in time between the present day and April 1990. In the present day we meet a middle-aged Danny Johnston, a long-in-the-tooth presenter of investigative television documentaries. He is past his peak professionally and clearly has some deep-rooted, well-suppressed emotional difficulties; the book opens with him crashing into a tree whilst drunk. He lives an empty life alone in London and is borderline alcoholic. His accident is well-publicised in the media and as a result he loses his television contract and is let go by his agent. With nothing to keep him in London he decides to return to the north, to Manchester where he grew up and where he began his career as a local radio reporter.

The book jumps back and forth in time between the present day and April 1990. In the present day we meet a middle-aged Danny Johnston, a long-in-the-tooth presenter of investigative television documentaries. He is past his peak professionally and clearly has some deep-rooted, well-suppressed emotional difficulties; the book opens with him crashing into a tree whilst drunk. He lives an empty life alone in London and is borderline alcoholic. His accident is well-publicised in the media and as a result he loses his television contract and is let go by his agent. With nothing to keep him in London he decides to return to the north, to Manchester where he grew up and where he began his career as a local radio reporter. I had that very experience recently with my book club when we decided to read To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf. Some of us had read it before (though years earlier) others had not read it at all. But even those of us who had read it before could not remember very much about it! I read it when I was studying for my English degree 30 years ago; I would probably have got through most of Virginia Woolf’s books in a very short space of time, because that was what my degree entailed – reading lots and lots of books very quickly! I always remembered that To The Lighthouse was my favourite, but I could not honestly have told you what happens in it, except that the journey to the eponymous lighthouse was about something desired more than something fulfilled.

I had that very experience recently with my book club when we decided to read To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf. Some of us had read it before (though years earlier) others had not read it at all. But even those of us who had read it before could not remember very much about it! I read it when I was studying for my English degree 30 years ago; I would probably have got through most of Virginia Woolf’s books in a very short space of time, because that was what my degree entailed – reading lots and lots of books very quickly! I always remembered that To The Lighthouse was my favourite, but I could not honestly have told you what happens in it, except that the journey to the eponymous lighthouse was about something desired more than something fulfilled.

Viktor E Frankl was a psychiatrist who is credited with developing one of the most important theories in the field human psychology (logotherapy) since Freud. He was developing his theory before he was captured by the Nazis but his time in the concentration camp enabled him to observe human beings in extreme conditions and further evolve his ideas.

Viktor E Frankl was a psychiatrist who is credited with developing one of the most important theories in the field human psychology (logotherapy) since Freud. He was developing his theory before he was captured by the Nazis but his time in the concentration camp enabled him to observe human beings in extreme conditions and further evolve his ideas. I was tempted to go for Haruki Murakami – after reading

I was tempted to go for Haruki Murakami – after reading  The novel begins in 1969 with the four children of the Gold family – Varya, Daniel, Klara and Simon – visiting a fortune-teller in her grimy downtown New York apartment, who is said to be able to predict the date of a person’s death. The mystic consults each child privately about their fate. Their reactions vary; Daniel, the second oldest, for example, says he thinks it is all rubbish. The younger children seem more vulnerable and more preoccupied, particularly Simon, who at this point is only seven years old, and who is told that he will die young.

The novel begins in 1969 with the four children of the Gold family – Varya, Daniel, Klara and Simon – visiting a fortune-teller in her grimy downtown New York apartment, who is said to be able to predict the date of a person’s death. The mystic consults each child privately about their fate. Their reactions vary; Daniel, the second oldest, for example, says he thinks it is all rubbish. The younger children seem more vulnerable and more preoccupied, particularly Simon, who at this point is only seven years old, and who is told that he will die young.

The book incorporates cognitive behavioural therapy techniques into exercises for addressing, for example tendencies to be self-critical. Low self-esteem can lead to debilitating inhibition, irrational fears, in both social and professional situations, and, I believe, can truly limit one’s life experience, achievement, enjoyment in life and personal relationships. I have found it really tough working through this book, particularly the chapters which focus on understanding the causes of poor self-esteem. Thinking about my relationship with my parents, in the aftermath of my mother’s death just a few months ago has not been easy.

The book incorporates cognitive behavioural therapy techniques into exercises for addressing, for example tendencies to be self-critical. Low self-esteem can lead to debilitating inhibition, irrational fears, in both social and professional situations, and, I believe, can truly limit one’s life experience, achievement, enjoyment in life and personal relationships. I have found it really tough working through this book, particularly the chapters which focus on understanding the causes of poor self-esteem. Thinking about my relationship with my parents, in the aftermath of my mother’s death just a few months ago has not been easy.