Time for my second Man Booker shortlist review and of the three I have read so far, my favourite. I wasn’t expecting to enjoy it as much as I did; the subject matter – a D-Day veteran suffering from PTSD – did not appeal particularly and when I saw the format – extended verse – I found my heart sinking slightly. That’s totally unfair, and I can in no way begin to justify that reaction other than to say I just love a good solid novel! I am delighted to say I was completely wrong, and I think it’s great when our prejudices and preferences are tested and we are pleasantly surprised.

The central character is Walker, a man from rural Nova Scotia, who fought with the Allied forces in the D-Day landings. He has seen and experienced terrible events, death and injury that most of us can barely even imagine, and he survived. After the end of the war, he goes back to the United States and finds himself living among the homeless in New York City. The book is divided into four sections: 1946, 1948, 1951 and 1953 each set in a different US city (though Los Angeles is the setting for both 1948 and 1953). As he reflects on his experiences, it becomes clear that it was impossible for him to return home to Canada. He reminisces about the quiet, gentle life he led there, where the rhythms of the seasons, the dependence on the harvests of the seas, and community events (such as village hall dances) dominate everyone’s existence. It’s as if the contrast between that life and the brutality he witnessed in the war means he fears contaminating the innocence of those he has left behind. He can never go back, never unsee what he has seen, and those he once loved will never be able to understand how he has been changed.

The central character is Walker, a man from rural Nova Scotia, who fought with the Allied forces in the D-Day landings. He has seen and experienced terrible events, death and injury that most of us can barely even imagine, and he survived. After the end of the war, he goes back to the United States and finds himself living among the homeless in New York City. The book is divided into four sections: 1946, 1948, 1951 and 1953 each set in a different US city (though Los Angeles is the setting for both 1948 and 1953). As he reflects on his experiences, it becomes clear that it was impossible for him to return home to Canada. He reminisces about the quiet, gentle life he led there, where the rhythms of the seasons, the dependence on the harvests of the seas, and community events (such as village hall dances) dominate everyone’s existence. It’s as if the contrast between that life and the brutality he witnessed in the war means he fears contaminating the innocence of those he has left behind. He can never go back, never unsee what he has seen, and those he once loved will never be able to understand how he has been changed.

In New York City, Walker lives among the vulnerable and the dispossessed. He is already suffering the effects of his PTSD:

“A dropped crate or a child’s shout, or car

Backfiring, and he’s in France again’

That taste in his mouth. Coins. Cordite. Blood.”

In 1948 Walker moves to Los Angeles and begins working on a city newspaper, initially writing film reviews, but then, as his profile grows and he earns respect among fellow journalists for his writing, he is given weightier projects. He persuades his Editor to let him do an extended investigation into homelessness. This takes him to San Francisco in 1951, and then back to LA in 1953. Walker is an observer, he seems to move on the periphery. He earns the trust of the cast of characters he befriends on the streets and his own personal trauma enables him to empathise with them:

“People; just like him.

Having given up the country for the city,

Boredom for fear, the faces

Gather here in these streets

Like spectators in a dream.

They wanted to be anonymous

Not swallowed whole, not to disappear.”

The final part of the book is the most intensely drawn. Walker recalls the devastation of older parts of the city, the traditional buildings, to make way for modern concrete highways and car parks, fuelled by corruption in the city authorities and mafia money. In the process many of the itinerant population were made homeless from whatever meagre shelter they had created for themselves and effectively thrown onto the scrap heap. The account of the destruction of the soul of the city is juxtaposed with vivid and detailed descriptions of the war:

“The side of a building fell like a tree.

Then the rest of it just collapsed

In on itself, immediately lost

In a dense cloud of brick dust;

The delay of the noise and shock waves.

There was an army there, pulling down everything north of 1st.

…

The sound of mortars like gravel on a metal slide; a running tear. Right next to me, young Benjamin took some shrapnel in the throat: his windpipe torn open, so he’s gargling blood and staring at me, fumbling at his neck like he feels his napkin is slipping.”

What is fascinating and moving about the work is how Walker’s wartime experiences have made him more human, more empathic, whereas those who live oblivious are consumed by inhumanity, lack of feeling for others and, in the case of the authorities, cruelty. America is failing those in need in the pursuit of economic growth, greed and modernism.

I thought I would find the verse structure annoying, but it is beautiful, as is the economy of Robertson’s language. It perfectly suits the slightly ethereal, enigmatic central character and his own relatively silent presence in the communities in which he moves and verse provides a way of creating the vivid imagery of his wartime recollections.

I recommend this book highly. Don’t be put off if you are not used to reading verse, you will get used to it quickly. An amazing piece of work.

What is your favourite book on the Man Booker 2018 shortlist so far?

If you have enjoyed this post, I would love for you to follow my blog. Let’s also connect on social media.

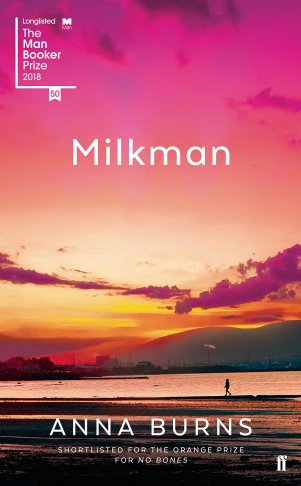

Milkman is set in Belfast during the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the central character and narrator is a young Catholic woman who finds herself drawn unwillingly into a relationship with a local paramilitary leader. It is not clear when the book is set, but I am guessing around the late 1970s, early ‘80s. Northern Ireland is known to be socially conservative, but the general sense of the place of women in society suggests to me that it dates back quite some time. Our central character (not named, I’ll come onto this) is from a large family. Her father is dead and she has several siblings, both older and younger. She is in a “maybe-relationship” with a local young man, who she has been seeing for about a year, though they have not made a commitment to one another. She is keen on running as a hobby and shares this with “third brother-in-law”. Whilst out running one day in a local park she finds that she is observed by a man in a white van. Over subsequent weeks he infiltrates her life by stealth, indicating that he expects her to have a relationship with him. He is known only as “Milkman”. It becomes clear to her that he is quite a powerful local figure in the paramilitary world, so not only does she have little choice about whether to become involved with him or not, it is made quite clear to her that as long as she goes along with him no harm will come to her “Maybe-boyfriend”.

Milkman is set in Belfast during the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the central character and narrator is a young Catholic woman who finds herself drawn unwillingly into a relationship with a local paramilitary leader. It is not clear when the book is set, but I am guessing around the late 1970s, early ‘80s. Northern Ireland is known to be socially conservative, but the general sense of the place of women in society suggests to me that it dates back quite some time. Our central character (not named, I’ll come onto this) is from a large family. Her father is dead and she has several siblings, both older and younger. She is in a “maybe-relationship” with a local young man, who she has been seeing for about a year, though they have not made a commitment to one another. She is keen on running as a hobby and shares this with “third brother-in-law”. Whilst out running one day in a local park she finds that she is observed by a man in a white van. Over subsequent weeks he infiltrates her life by stealth, indicating that he expects her to have a relationship with him. He is known only as “Milkman”. It becomes clear to her that he is quite a powerful local figure in the paramilitary world, so not only does she have little choice about whether to become involved with him or not, it is made quite clear to her that as long as she goes along with him no harm will come to her “Maybe-boyfriend”. One thing that is so impressive about Chevalier is how beautifully she creates the historical setting: the two novels I have read so far have been set in 17th century Holland and 15th century Paris and Brussels and I can only begin to imagine the amount of research she has to undertake. The Last Runaway is set in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century when parts of the country were only just being settled. Honor Bright, our main character is a young Quaker woman from Dorset in England. She has led a modest and sheltered life, but her world was turned upside down when her fiancé left her and their close-knit Quaker community for another woman. This was not only a scandal but it left Honor distraught and in a very difficult position. When her sister, Grace, is persuaded by her fiancé that they should move to America, Honor decides she must go with her, not only to support her sister, but to escape the oppression of her situation and have some chance of making a life for herself.

One thing that is so impressive about Chevalier is how beautifully she creates the historical setting: the two novels I have read so far have been set in 17th century Holland and 15th century Paris and Brussels and I can only begin to imagine the amount of research she has to undertake. The Last Runaway is set in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century when parts of the country were only just being settled. Honor Bright, our main character is a young Quaker woman from Dorset in England. She has led a modest and sheltered life, but her world was turned upside down when her fiancé left her and their close-knit Quaker community for another woman. This was not only a scandal but it left Honor distraught and in a very difficult position. When her sister, Grace, is persuaded by her fiancé that they should move to America, Honor decides she must go with her, not only to support her sister, but to escape the oppression of her situation and have some chance of making a life for herself.

The plot is not complicated: ‘Swede’ Levov is a third generation Jewish immigrant whose grandfather came to America from Europe. He was a glovemaker and set up a business in Newark, New Jersey which became highly successful. Swede’s father continued the business, which peaked in the 1950s and 1960s when glove-wearing for respectable women was the norm and most would have several pairs. (There is more information on gloves in this book than you will ever need to know, but it’s fascinating!) Swede inherited the business from his father, while his more wayward brother became a cardiac surgeon.

The plot is not complicated: ‘Swede’ Levov is a third generation Jewish immigrant whose grandfather came to America from Europe. He was a glovemaker and set up a business in Newark, New Jersey which became highly successful. Swede’s father continued the business, which peaked in the 1950s and 1960s when glove-wearing for respectable women was the norm and most would have several pairs. (There is more information on gloves in this book than you will ever need to know, but it’s fascinating!) Swede inherited the business from his father, while his more wayward brother became a cardiac surgeon.

I chose this book for my 2018 Facebook Reading Challenge. The June theme was an autobiography, a tricky category since enjoyment can often depend on your feelings about the author. I also wanted to avoid titles that would most likely have been ghost-written. After thinking about it for some time, I chose this, the first volume in Angelou’s memoir series, and the one which is often considered to be the best. It can be read as a stand-alone.

I chose this book for my 2018 Facebook Reading Challenge. The June theme was an autobiography, a tricky category since enjoyment can often depend on your feelings about the author. I also wanted to avoid titles that would most likely have been ghost-written. After thinking about it for some time, I chose this, the first volume in Angelou’s memoir series, and the one which is often considered to be the best. It can be read as a stand-alone.

Browsing in the bookshop last year, I noticed that she had published her own autobiography, at the age of 83 – I note with some pleasure that her 84th birthday is in fact today! Many happy returns! Reading the blurb whetted my appetite – I was not aware of her life as a groundbreaking Literary Editor at the Sunday Times, or that she had five children, including one boy who died as a baby, and another son who was born with severe disabilities, nor that her first husband, fellow journalist Nicholas Tomalin, was killed in 1973, when her children were still very young. It sounded like a very interesting read.

Browsing in the bookshop last year, I noticed that she had published her own autobiography, at the age of 83 – I note with some pleasure that her 84th birthday is in fact today! Many happy returns! Reading the blurb whetted my appetite – I was not aware of her life as a groundbreaking Literary Editor at the Sunday Times, or that she had five children, including one boy who died as a baby, and another son who was born with severe disabilities, nor that her first husband, fellow journalist Nicholas Tomalin, was killed in 1973, when her children were still very young. It sounded like a very interesting read. The novel is set in Renaissance Florence; the sense of time and place is profound. You can almost smell the streets wafting from the pages! Dunant is a meticulous researcher and the novel feels very authentic. The central character is Alessandra, the fifteen year-old daughter of a wealthy cloth merchant. Much to the frustration of her family Alessandra is a precociously intelligent young woman, a talented artist, a strong personality and has a deep desire to be out in the world. These are all traits which are highly inconvenient for the family and not compatible with the kind of life she will be expected to lead.

The novel is set in Renaissance Florence; the sense of time and place is profound. You can almost smell the streets wafting from the pages! Dunant is a meticulous researcher and the novel feels very authentic. The central character is Alessandra, the fifteen year-old daughter of a wealthy cloth merchant. Much to the frustration of her family Alessandra is a precociously intelligent young woman, a talented artist, a strong personality and has a deep desire to be out in the world. These are all traits which are highly inconvenient for the family and not compatible with the kind of life she will be expected to lead.