It was back in the summer that I published my first post in what was intended as an occasional series on building a library of books for your children. Last time I focussed on the 2-5 age group, mainly picture books and mainly classics. This time I am moving on a little to the 4-7 age group, ie Key Stage 1. This is the age when children are just learning to read, but they still value and need to be read to – the phonics and early reading books are much better than they used to be (I loved reading the Oxford Reading Tree Biff, Chip and Kipper books that my kids brought home from school), but they are designed to expose your children to vocabulary, word order and sentence construction – they are tools designed specifically to aid learning; good children’s literature, on the other hand, fosters joy, builds a bond between child and reader and should inspire.

There are some good chapter books now for six and seven year olds: precocious readers who benefit from the challenge of something more complex, but still need age-appropriate themes and subject-matter. I would argue, however, that at this age pictures are still vitally important. Pictures help to build vocabulary organically, they give the child something to look at and focus on whilst listening, as they may not be able to read all of the words themselves, and they help the child develop their imaginative skills as they look at the visions created for them by authors and illustrators. For this age group, the quality of the illustration is just as important as the text; can you imagine AA without EH, or Julia without Axel?

So, for those of you looking to build a library for the child or children in your lives, here are my top ten suggestions. The list is (absolutely!) not exhaustive of course, but these ten will provide the foundation for something wonderful. Nearly all of the books below are just one in a series or the same authors have written similar titles that you can add to the collection.

- The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter (plus the other 22 books in her classic collection!)

- The Mr Men and Little Miss series by Roger Hargreaves

- Winnie-the-Pooh by AA Milne

- The Cat in the Hat by Dr Seuss

- The Story of Babar by Jean de Brunhoff

- Finn Family Moomintroll by Tove Jansson

- Room on the Broom by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler

- Look Inside – Things That Go by Rob Lloyd Jones and Stefano Tognetti

- The Snowman by Raymond Briggs

- The Jolly Postman by Janet and Allan Ahlberg

I would love to hear your suggestions of books for this age group, particularly any that you have enjoyed sharing with the little people in your life.

I would love to hear your suggestions of indispensable titles for 4-7 year olds.

If you have enjoyed this post, I would love for you to follow my blog. Let’s also connect on social media

The Lathe of Heaven was written in 1971, but was set in ‘the future’ – Portland Oregon in 2002. This future world is one in which the global population is out of control, climate change has wrought irreparable damage and war in the Middle East threatens geopolitical stability. The most alarming (and engaging) thing about the book, for me, was how prophetic it was; in 1971 did readers think this was some dystopian world? Worryingly, many of the problems envisaged by Le Guin are recognisable features of our environment in 2019.

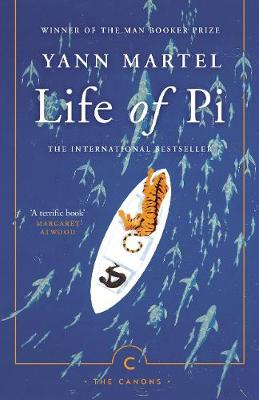

The Lathe of Heaven was written in 1971, but was set in ‘the future’ – Portland Oregon in 2002. This future world is one in which the global population is out of control, climate change has wrought irreparable damage and war in the Middle East threatens geopolitical stability. The most alarming (and engaging) thing about the book, for me, was how prophetic it was; in 1971 did readers think this was some dystopian world? Worryingly, many of the problems envisaged by Le Guin are recognisable features of our environment in 2019. The story is well-known: a young Indian boy, Piscine “Pi” Patel (a name he adopts to get back at the school bullies who taunt him with the nickname ‘Pissing’) grows up in the territory of Pondicherry where his parents own a zoo. The first part of the story gives us a detailed account of the family’s life there, including enormous detail about life for the animals in a zoo setting (I was fascinated by this and it changed my perspective on zoos). We learn in particular about the fierce Bengal tiger, Richard Parker, who is the zoo’s prized possession. I love the use of ‘naming’ in this book – the story of how Richard Parker came to be given this name is brilliant and a sign of the author’s ingenuity and creativity. The other important feature of this part of the novel is that we learn of Pi’s deeply philosophical nature, his decision to adopt three religions (Hinduism, in which he has been brought up, Islam and Christianity), much to his family’s dismay, because he can see benefits in all of them.

The story is well-known: a young Indian boy, Piscine “Pi” Patel (a name he adopts to get back at the school bullies who taunt him with the nickname ‘Pissing’) grows up in the territory of Pondicherry where his parents own a zoo. The first part of the story gives us a detailed account of the family’s life there, including enormous detail about life for the animals in a zoo setting (I was fascinated by this and it changed my perspective on zoos). We learn in particular about the fierce Bengal tiger, Richard Parker, who is the zoo’s prized possession. I love the use of ‘naming’ in this book – the story of how Richard Parker came to be given this name is brilliant and a sign of the author’s ingenuity and creativity. The other important feature of this part of the novel is that we learn of Pi’s deeply philosophical nature, his decision to adopt three religions (Hinduism, in which he has been brought up, Islam and Christianity), much to his family’s dismay, because he can see benefits in all of them. The Booker prize winner(s) were announced last week and for the first time in years, and against the explicit rules of the contest, the judges awarded the prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. I have not read either book yet, though I am currently listening to The Testaments on the excellent BBC Sounds and enjoying it enormously, though it is extremely dark. There has been so much publicity around Atwood and The Testaments that I was wondering how on earth the Booker prize judges were going to be able to not award it to her! So, I think the judges probably made the right decision. By now, I would probably have worked my way through at least two thirds of the shortlist (I’ve never managed all six in the period between shortlist and winner), but, for obvious reasons, I have not read that much so far this year.

The Booker prize winner(s) were announced last week and for the first time in years, and against the explicit rules of the contest, the judges awarded the prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. I have not read either book yet, though I am currently listening to The Testaments on the excellent BBC Sounds and enjoying it enormously, though it is extremely dark. There has been so much publicity around Atwood and The Testaments that I was wondering how on earth the Booker prize judges were going to be able to not award it to her! So, I think the judges probably made the right decision. By now, I would probably have worked my way through at least two thirds of the shortlist (I’ve never managed all six in the period between shortlist and winner), but, for obvious reasons, I have not read that much so far this year. It is somewhat and sadly ironic that I was reading Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World at the time of my mother’s death, a novel about a woman, Leila, an Istanbul prostitute known as Tequila Leila, who is brutally murdered in a back alley by street thugs. Rather than death being an instant occurrence, however, the author explores the idea of it as a transition from the world of the living to the ‘other’ (with a duration, for Leila, of ten minutes and thirty-eight seconds) during which time her whole life flashes before her. Leila’s life story is told through a series of recollections about her five closest friends, how and when she met them and what impact they have had on her life. We learn that Leila came from a relatively affluent family. Her father was anxious for heirs, but when his wife proved incapable of having any he took a second wife, Binnaz, a much younger woman from a lowly family, who gave birth to Leila. Binnaz was forced to give up the child to the first wife to bring up as if she were her own, whilst Binnaz, who never recovered mentally from the trauma of that event, was thereafter known to Leila as ‘Auntie’.

It is somewhat and sadly ironic that I was reading Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World at the time of my mother’s death, a novel about a woman, Leila, an Istanbul prostitute known as Tequila Leila, who is brutally murdered in a back alley by street thugs. Rather than death being an instant occurrence, however, the author explores the idea of it as a transition from the world of the living to the ‘other’ (with a duration, for Leila, of ten minutes and thirty-eight seconds) during which time her whole life flashes before her. Leila’s life story is told through a series of recollections about her five closest friends, how and when she met them and what impact they have had on her life. We learn that Leila came from a relatively affluent family. Her father was anxious for heirs, but when his wife proved incapable of having any he took a second wife, Binnaz, a much younger woman from a lowly family, who gave birth to Leila. Binnaz was forced to give up the child to the first wife to bring up as if she were her own, whilst Binnaz, who never recovered mentally from the trauma of that event, was thereafter known to Leila as ‘Auntie’. The book concerns two women, Rosemary, an 86 year-old widow, and Kate, a 26 year-old journalist, and how they are brought together by chance when the Brixton lido is threatened with closure. Their relationship evolves as together they mount a campaign to keep the pool open, drawing in other local people and reviving a community spirit that everyone involved thought had been lost. In some ways the two women could not be more different: Rosemary is nearing the end of her life, now alone having lost her beloved husband, and has lived in this area of South London all her life. Kate, on the other hand, is young and bright, and has moved to the city from Bristol to begin her journalistic career on the local paper. Kate too, though, is lonely; unlike Rosemary she has not lost anyone, but she has not found anyone either, and she grapples with panic attacks, anxiety and low self-esteem. She shares a house with a number of similarly isolated flatmates, none of whom she knows, and stays alive thanks to ready meals.

The book concerns two women, Rosemary, an 86 year-old widow, and Kate, a 26 year-old journalist, and how they are brought together by chance when the Brixton lido is threatened with closure. Their relationship evolves as together they mount a campaign to keep the pool open, drawing in other local people and reviving a community spirit that everyone involved thought had been lost. In some ways the two women could not be more different: Rosemary is nearing the end of her life, now alone having lost her beloved husband, and has lived in this area of South London all her life. Kate, on the other hand, is young and bright, and has moved to the city from Bristol to begin her journalistic career on the local paper. Kate too, though, is lonely; unlike Rosemary she has not lost anyone, but she has not found anyone either, and she grapples with panic attacks, anxiety and low self-esteem. She shares a house with a number of similarly isolated flatmates, none of whom she knows, and stays alive thanks to ready meals. It seems appropriate that I should be posting a review of Normal People this week, a book so very much about Ireland, the challenges and contradictions at the heart of a nation that has transformed itself in recent years. It is not just about Ireland, but about what it means to be young in Ireland and about class. It is also about identity and, in common with some of the issues faced in the UK and many other societies I am sure, the draw away from regional towns and cities, towards a centre, a capital, where there is perceived to be more opportunity, and what that means both for the individual and for society in the wider sense.

It seems appropriate that I should be posting a review of Normal People this week, a book so very much about Ireland, the challenges and contradictions at the heart of a nation that has transformed itself in recent years. It is not just about Ireland, but about what it means to be young in Ireland and about class. It is also about identity and, in common with some of the issues faced in the UK and many other societies I am sure, the draw away from regional towns and cities, towards a centre, a capital, where there is perceived to be more opportunity, and what that means both for the individual and for society in the wider sense. I have chosen a book which caught my eye a couple of months ago – The Lido by Libby Page. It concerns a friendship between two women, 86 year-old widow Rosemary and 26 year-old Kate, who strike up a bond when their local outdoor swimming pool in Brixton, south London, is threatened with closure. The two women have different reasons for wanting to campaign to keep the lido open, but they are brought together in a common cause.

I have chosen a book which caught my eye a couple of months ago – The Lido by Libby Page. It concerns a friendship between two women, 86 year-old widow Rosemary and 26 year-old Kate, who strike up a bond when their local outdoor swimming pool in Brixton, south London, is threatened with closure. The two women have different reasons for wanting to campaign to keep the lido open, but they are brought together in a common cause. The centre of the story is the relationship between two women, Bel and Lydia, who meet at a New Year’s party in 1985, when they are both sixth-formers although at different schools in Yorkshire. They are very different people – Lydia is reserved, generally quite sensible, and from a secure and ordinary family. Bel is wilder, her family rather more bohemian and she has a difficult relationship with her parents. Bel grew up in France and then London and it is her father’s job that has brought them to northern England, where she is something of an outsider. Bel and Lydia are drawn to one another, despite their very different personalities; for Lydia, Bel represents spontenaiety, excitement, danger even. For Bel, Lydia represents security, a steady point in a turning world.

The centre of the story is the relationship between two women, Bel and Lydia, who meet at a New Year’s party in 1985, when they are both sixth-formers although at different schools in Yorkshire. They are very different people – Lydia is reserved, generally quite sensible, and from a secure and ordinary family. Bel is wilder, her family rather more bohemian and she has a difficult relationship with her parents. Bel grew up in France and then London and it is her father’s job that has brought them to northern England, where she is something of an outsider. Bel and Lydia are drawn to one another, despite their very different personalities; for Lydia, Bel represents spontenaiety, excitement, danger even. For Bel, Lydia represents security, a steady point in a turning world. This book has been on my to-read list for some time now, ever since it caught my eye over a year ago when it was published. I recommended it as a

This book has been on my to-read list for some time now, ever since it caught my eye over a year ago when it was published. I recommended it as a  The story begins when 15 year-old Michael, off school for many months after contracting hepatitis, seeks out Hanna Schmitz, a woman who had been passing when he found himself being sick in the street and who had helped him. Once he is well again, Michael’s mother sends him off to find the mystery good Samaritan in order that he can thank her. Hanna is twenty years Michael’s senior and employed as a bus conductor, but despite the social and age gap between them, they begin a passionate affair, both parties equally consenting. One of the more intimate aspects of their relationship is that Michael reads aloud to Hanna, after sex and in the bath mainly, although never the other way around. Michael never questions Hanna’s desire to have him read to her, he just accepts it. This makes up the first part of the book and perhaps it is a testament to events that have occurred since the time of its writing that all of us (mothers of teenagers!) found the prose rather discomfiting, and not a little implausible. Hanna disappears mysteriously out of Michael’s life, leaving him heartbroken and perhaps also rather damaged.

The story begins when 15 year-old Michael, off school for many months after contracting hepatitis, seeks out Hanna Schmitz, a woman who had been passing when he found himself being sick in the street and who had helped him. Once he is well again, Michael’s mother sends him off to find the mystery good Samaritan in order that he can thank her. Hanna is twenty years Michael’s senior and employed as a bus conductor, but despite the social and age gap between them, they begin a passionate affair, both parties equally consenting. One of the more intimate aspects of their relationship is that Michael reads aloud to Hanna, after sex and in the bath mainly, although never the other way around. Michael never questions Hanna’s desire to have him read to her, he just accepts it. This makes up the first part of the book and perhaps it is a testament to events that have occurred since the time of its writing that all of us (mothers of teenagers!) found the prose rather discomfiting, and not a little implausible. Hanna disappears mysteriously out of Michael’s life, leaving him heartbroken and perhaps also rather damaged.